July 2007

During the second half of summer, our banding station operated on 23 days. We banded 679 birds of 55 species and processed 183 recaptured birds. Our total effort (1,820 net hours) was similar to June, when less than half as many (274) birds were banded, so the capture rate during the latter part of the summer period more than doubled to 37.3 new birds per 100 net hours. Locally breeding adults (usually in heavy molt) and young (Hatching Year) birds comprised most of our catch. And, except for Red-eyed Vireo and Cedar Waxwing, HY birds dominated our totals for most species.

The most commonly banded species during the second half of summer were American Redstart (96), Gray Catbird (89), Cedar Waxwing (63), Common Yellowthroat (46), Red-eyed Vireo (35), Hooded Warbler (34), Wood Thrush (32), Song Sparrow (28), Scarlet Tanager (20), and Veery (19). Our total for the period also included a number of early "fall" migrants, such as Least Flycatcher, Yellow Warbler, and Northern Waterthrush, distinguishable by their visible fat deposits. Our best banding days occurred at the beginning (7/5: 49 birds of 11 species) and the end of the period (8/2: 48 birds of 21 species). The former was greatly helped by an influx of Cedar Waxwings; the latter, by Gray Catbirds and Red-eyed Vireos.

Overall, the summer 2007 total of 953 birds banded was above (but not statistically so) our long-term average of 733, but it was well below our maximum summer banding total of 1,500 recorded in 2004. Similarly, the summer 2007 species total of 57 was close to the long-term average (~59) but well below the highest count of 78 species in 1998.

Most species were banded in statistically average numbers this summer (i.e., within one standard deviation of the long-term, 1961-2006, mean). No species were below average, but the following 17 species (out of 57 examined) were > 1 S.D. above the long-term average: Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Least Flycatcher, Veery, Wood Thrush, Gray Catbird, Cedar Waxwing, Chestnut-sided Warbler, Magnolia Warbler, Black-throated Blue Warbler, Cerulean Warbler, American Redstart, Kentucky Warbler, Common Yellowthroat, Hooded Warbler, Scarlet Tanager, Northern Cardinal, and Red-winged Blackbird. Fifteen species with long-term summer season averages > or = 1 were missed (e.g., Eastern Wood-Pewee, Great Crested Flycatcher, Blue-winged Warbler, Chipping Sparrow, and both cuckoos); conversely, we banded nine species with long-term averages <1 (e.g., Swainson's Thrush, Worm-eating Warbler, and Orchard Oriole). A Cooper's Hawk banded on July 17 was an addition to our all-time summer banding list, which now stands at 122 species. Click here to see all our summer 2007 totals compared to their associated long-term averages, minima, and maxima.

We thank Mary and Alex Shidel, Pam Ferkett, Matt Shumar, Sally McDermott, Annie Lindsay, Mike Allen, Trish Miller, and Jean Rothe for their help with banding in July.

Many adults are in heavy molt in July as they begin to replace their entire plumage. Because of the demands of nesting, some of these birds, especially SY birds whose flight feathers are older, are in dire need of molt!

This Indigo Bunting (SY female) exemplified the need for molt! At the time of capture (July 5th), she still had a brood patch and had not begun molting, but, as you'll read below, other birds with shorter nesting seasons were already doing so.

American Redstarts are one of the earliest species to undergo their prebasic (i.e., post-breeding) molt. An SY-M AMRE (top photo to left), had a molt score of 62 (out of 90) on July 17th, compared to a fresh AHY male (bottom photo to left) which already had completed its molt (molt score = 90) as of August 5th.

Although we can't be sure, the early date of its molt completion suggests that it, too, was an SY-M (all traces of its female-like SY plumage having been replaced), because this age class generally has much lower breeding success than adult (ASY) males.

We captured several molting Chestnut-sided Warbler adults this month, including these two SY females with molt scores of 16 and 31, respectively.

This molting SY male Northern Parula was only the second of its species banded this year. Birds in their second year tend to look more worn because much of their plumage is retained juvenal and, therefore, older than that of ASY birds, which replaced all flight feathers during the previous year's prebasic molt.

Compare the very brown retained juvenal secondaries on this NOPA (bottom photo below) with its recently molted primaries. Also note the molt limit between the alula covert (A1) and A2. A1 molted last fall during the bird's partial first prebasic molt. The existence of this molt limit is how we were able to age it as an SY.

Once the old alula feathers are dropped, near the end of the bird's current molt, there will be no way to distinguish it as an SY any longer, and it would have to be aged less precisely as an AHY. The molt score for this bird was 40.

We regularly capture Swainson's Thrushes during the late summer period in early stages of molt-migration, a phenomenon originally described in the literature by Jeff Cherry (Wilson Bulletin 97:368-370).

In fact, this species is one of only a handful that will occasionally overlap its molt with migration. SWTHs do not nest closer than about 100 miles from Powdermill, so in all likelihood this SY bird (note the buffy "teardrops" on its retained juvenal greater and median coverts) moved a considerable distance following nesting (or a nesting attempt) before its molt began. Such birds may continue to migrate while actively molting (rarely, molting birds are among active migrants killed at night by colliding with tall communications towers, as reported by Jeff Cherry and Kenneth C. Parkes; Wilson Bulletin 95:621-627), or else they may initiate and/or complete their molt in an area south of their breeding grounds.

As documented in an extensive series of papers by Seivert Rohwer and his students, in the Great Basin region of the American West, where arid conditions on the breeding grounds in late summer are not especially conducive to molting, adults of several species routinely migrate substantial distances to special molting areas. In general, their movement away from increasingly drought-stricken breeding habitats is timed for their arrival somewhere in the desert Southwest or Mexico during the period of monsoon rains. The flush of insects associated with these rains constitutes a bumper-crop resource for the energy-and protein-demanding molt process.

In contrast to the many worn and molting (= motley!) adults, many young warblers are in very fresh plumage at this time of year. Compare the adult (SY) and young (HY) male Black-throated Green Warblers captured on July 17th.

Look especially at the condition of their alula and primary coverts. The young BTNW is still in active first prebasic molt with some still unmolted juvenal head feathers and actively growing greater (i.e., secondary) coverts.

These two Magnolia Warblers captured together on July 29th--a freshly feathered HY female (top bird in the photo to left) and what probably is its very bedraggled mother, an SY female (bottom bird; molt score = 12) provide a striking, but commonly observed contrast in plumage condition between adults and their young at this time of year.

Here are some more examples of HY warblers in fresh first basic plumage

From top to bottom:

male Blackburnian Warbler,

male Black-throated Blue Warbler and female Canada Warbler

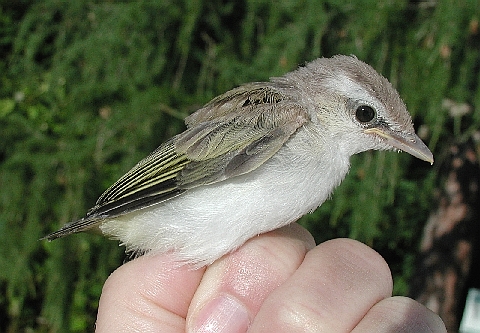

July is also the month for baby birds. Juveniles are easily distinguished from adults by a number of characteristics. One sign is the "pouty mouth," the fleshy bright-colored gape, a nestling trait that is often retained for several weeks after fledging.

This characteristic was very evident on this "Local," i.e., barely flighted, Red-eyed Vireo, one of the youngest we have ever seen in our nets!

On July 8th, we banded an HY Barn Swallow and an HY Tree Swallow; the BARS had a much more obvious fleshy gape.

Another definitive characteristic of juvenal plumage is loosely textured feathers. Juvenal feathers have many fewer interlocking barbules and, therefore, looser barbs, giving them a very fuzzy appearance.

This is especially noticeable on nape and back feathers, and also on undertail coverts, as pictured below. Can you guess to which bird species each of these fuzzy bottoms belongs? Hint: the photos are not to scale!

Answer to fuzzy bottoms quiz (left to right): Common Yellowthroat, House Wren, Brown Thrasher, Gray Catbird

Eye color is another useful criterion for ageing certain species, especially those with dark or brightly colored eyes as adults. In these species the eye color of the juveniles usually is duller, browner, or grayer than that of adults.

For instance, this characteristic is useful (often into the fall) for ageing Mimids (catbirds, mockingbirds, and thrashers), vireos (look again at the brown-eyed juvenile Red-eyed Vireo pictured above), and many other species.

This Brown Thrasher banded on 7/22 had a milky gray iris characteristic of juveniles, compared to the bright yellow eye of adults.

The juvenile Eastern Towhee (HY male) has a brown eye compared to the dark red eye of adults

Just some gratuitous "baby" portraits:

Top: Tufted Titmouse HY U (7/26)

Middle: Downy Woodpecker HY M (7/08)

Bottom: Northern Cardinal HY U (7/05)

During the first couple weeks of July, baby thrushes were all over the place. We caught mostly Wood Thrushes (bottom picture on left), but there were also many American Robin (top picture to left) and Veery (middle picture to left) fledglings. Again, note their "pouty" appearance!

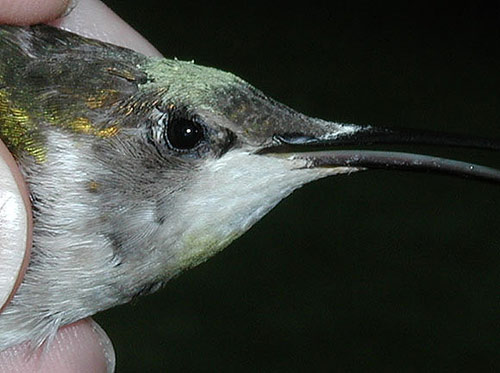

An adult female Ruby-throated Hummingbird banded on July 24th had heavy greenish-white pollen residue on her crown and also on her throat.

It is not the pollen signature left by cardinal flower or spotted jewelweed--we're familiar with those. If you have an idea what kind of flower would leave pollen of this color in these spots, please let us know!

Also unusual was this HY Gray Catbird banded on 8/1, with a dozen red ants clamped onto its tail feathers. A case of anting gone awry perhaps?

As mentioned above, we caught a few species that are quite often missed in a given summer, including this SY male Worm-eating Warbler on 7/5, and this HY male Orchard Oriole on 8/2 (sexed based on wing length, 76.0mm).

Finally, an adult (ASY) male Cooper's Hawk was, literally, a BIG surprise in the nets on 7/17 (wing length 239.0mm; body mass, 314.5g).

Unfortunately, photos of the bird did not turn out, but it left a souvenir body feather pictured to the left.

As always, we enjoyed providing banding demonstrations to Powdermill summer campers.

This group of outdoor explorers (ages 9-12) visited on July 18. Although they enjoyed seeing birds up-close, they were clearly entranced by 14-year old "Puppy" Mulvihill.

Before you turn from this page, with its focus on molts and plumages, Bob Mulvihill would like to offer this tribute to one whose insights forever changed the way in which we study and discuss these subjects...

Pictured to the left is Ken Parkes and Bob Mulvihill viewing a possible Old World Tundra (Bewick's) Swan

at Donegal Lake near Powdermill in December 1982.

Pictured to the left is Bob Mulvihill, Ken Parkes, and artist/writer, Julie Zickefoose, following her presentation at the Three Rivers Bird Club monthly meeting in Pittsburgh in February 2007. Ken was a long-time friend and big fan of Julie's (and vice versa), so special arrangements were made to get him to this meeting.

One of the most important chapters in the study of molts and plumages, and in the history of the Powdermill banding program, came to a close on July 16, 2007 with the passing of a legendary ornithologist, Dr. Kenneth C. Parkes, who had been receiving care in a nursing home for the last few years. Born August 8, 1922 in Hackensack, New Jersey, he completed both his undergraduate and graduate studies at Cornell University. He received his doctorate in 1952 for research on The Birds of New York State and Their Taxonomy, which resulted in a 612-page thesis in two parts (non-passerines and passerines).

Dr. Parkes had a 43-year career with the Section of Birds of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, from 1953 until his retirement in 1996. For more than 30 of those years, he was its Senior Curator, and for many years after his retirement, before suffering a stroke and becoming ill with Parkinson's disease, he maintained his office in the section and was a very active Curator Emeritus, working in the bird range and continuing to work and collaborate on technical papers, including one published as recently as 2001.

Along with his Assistant Curator, Dr. Mary Heimerdinger Clench (and later, Dr. D. Scott Wood), he directed a nascent Powdermill banding program and mentored its original Bander-in-Charge, Robert Leberman (and later, Bob Mulvihill). Through the years, his influence and example, and that of his curatorial assistants, insured that Powdermill's banding program would collect data of value for scientific research on many fronts.

Ken Parkes was one of modern ornithology's true masters and one of its true characters, and he will forever be one of its "Grand Old Men." Out of his more than 500 scholarly contributions to the professional ornithological literature, one in particular stands out as being among the most influential of the twentieth century. Co-authored in 1959 with Philip S. Humphrey, his colleague from Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History, An Approach to the Study of Molts and Plumages (Auk 76:1-31) proposed the first tenable scientific framework and terminology for describing and understanding the evolution of molts and patterns of plumage succession across a wide range (both taxonomically and geographically speaking) of bird groups.

This seminal paper and the semantics of the Humphrey-Parkes molt terminology--the now very familiar terms like basic, alternate, supplemental, and definitive plumages--have been a tour de force not only for advancing evolutionary studies of molt, but also for increasing the accuracy and precision of field and in-hand bird identifications.

Ken was famous (some might say, infamous!) for being unabashedly direct with criticism, which he hardly ever gave a thought to sugar-coating, and which almost invariably (and frustratingly, for some) was well-founded. Those of us who knew him well think that Ken sometimes was purposely "bad" simply as a strategy or rhetorical device for making a perfectly "good" point that then couldn't be missed by anyone or, just as importantly, misattributed to anyone else.

It can be said that Ken took almost childish delight in being right and could not resist the temptation to set the record straight about birds, whether it was a technical point in avian taxonomy, a fine point of identification (or misidentification) of a bird seen locally in western Pennsylvania, or a small factual error or missing detail accompanying a popular article about birds in a magazine or newspaper. As a professional ornithologist, I'm quite sure that Ken holds the record for penning more letters-to-the-editor than anyone!

He also penned innumerable book reviews for the leading ornithological journals, and he literally wrote the book "On the Role of the Referee" (Auk 115: 1079-1080), an invaluable professional role that he knew very well, having served in that capacity hundreds of times for dozens of scientific journals, book editors and would-be authors over the course of his long career.

All of this is not to say that Ken was hyper-critical. He wasn't. If something that somebody did deserved praise in his estimation, then he was as quick and generous with that as he was with criticism. He was the first to give credit where credit was due; he expected (even insisted) on the same in return. I feel lucky to have earned Ken's praise from time to time during my 25-year career with Carnegie Museum; I feel equally lucky to have learned from his criticisms and corrections. One thing is for sure, if a draft manuscript of mine made it past Ken's pre-submission review, I usually had little to worry about from editors and referees!

Ken respected and greatly encouraged the contributions of amateurs to the science of ornithology, a tradition that he helped to formalize and which embodies the mission of his alma mater, Cornell University and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, now a global leader for "citizen science." Ken's appreciation of birds was not only intellectual--it also expressed itself in his admiration of those who had good field birding skills, his appreciation of good bird art, and his own simple love of bird-watching. Ken was as well known and well-liked by the community of bird watchers and bird artists in his own backyard as he was admired and well-respected for his significant and always scholarly scientific contributions by ornithological colleagues around the world.

In short, Ken was an ornithologist's ornithologist, a curator's curator, a birder's birder, and a bird artist's very discerning and appreciative critic. His life-time contribution to all things avian was, to say the least, monumental. Dr. Kenneth C. Parkes was, if not one-of-a-kind, then surely a very rare (and wonderful) bird, and I feel signally fortunate and proud to be able to include him on my life list.

In the words of Pastor David Herndon, who eulogized Ken in a memorial service at the First Unitarian Church of Pittsburgh on July 28, "Our world could use more individuals...whose lives are innocently devoted to learning about the world, individuals who deeply love and appreciate the natural world, individuals whose pursuits do not harm or exploit anyone, individuals who leave behind a legacy of carefully researched understanding and thoughtful service...We will miss Kenneth Parkes." Yes, we will.