Late May 2007

During the final full week of the 2007 spring banding season at Powdermill, we banded just 127 birds of 32 species (including, however, one exciting new species for the season) and processed 48 recaptures, with a total effort of 1,165 net-hours (giving a very low capture rate of just 11 new birds per 100 net-hours).

Our banding total did not exceed 30 birds on any day this week, and our species diversity maxed out at just 15. By comparison, the best single banding day this spring (only a couple weeks ago on May 17) netted us 170 new birds of 40 species!

The shape of spring migration (plotted in the graph to your left), with its gradual build-up to a peak in number and variety of birds over the course of 10 weeks, followed by a rapid decline in banding and species totals in just two weeks time, resembles an exciting roller-coaster ride!

The top five species this week were Cedar Waxwing (35 banded), Gray Catbird (16), Red-eyed Vireo (12), Acadian Flycatcher (6), with American Goldfinch, "Traill's" (i.e., Alder and Willow) Flycatcher, and Ruby-throated Hummingbird tied for fifth place with five of each banded. Our overall total for spring 2007 was 2,822 birds of 102 species banded, both of which statistics are very close to the long-term averages at Powdermill of 2,764 and 97.

Our thanks to Pam Ferkett, Mary Shidel, Michael Allen, Bob Leberman, Danilo Mejila, Maria Paulino, and Brent Worls for their help with the banding this week.

Not surprisingly, the past week of banding bridged the always blurry boundary between the migration and breeding seasons at Powdermill. This was evidenced by the capture of non-breeding species, like Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, that clearly belong in the former category...

The spread wing pictured to your left belonged to a second-year (SY) YBFL banded on 6/1. Note the eccentric molt limit between the block of six brownish retained juvenal outer secondaries and inner primaries and the surrounding dark dusky-gray molted inner secondaries and outer primaries (look also at the difference in the brownish vs. blackish feather shafts between the retainedand molted flight feathers).

...and an HY House Finch, equally clearly a product of the latter! Banded on 6/3, this immature House Finch (the sex of this species is unknown in its juvenal plumage) is our first HY bird of the year.

Two warblers banded on 5/29 showed how variable the condition of feathers can be when birds return to their breeding grounds in spring. This is a product of how much prealternate body molt a bird has undergone, as well as how physically abrasive the environment was where a bird overwintered.

The ASY male Kentucky Warbler (top photo to your left) was in very fresh plumage, while the SY female Black-throated Green Warbler banded on the same day was exceedingly worn

On the last day of the week, we banded an SY female Blue-winged Warbler. All the warblers in the genus Vermivora are, to one degree or another, specialized "branch-tip" foragers with the ability to use their thin sharp beaks to pry open and into terminal buds, leaves, and flowers in search of small insects. When we band these species, we often demonstrate the interesting bill opening action by having a visitor use their fingers to try and lightly close one of these bird's bills.

Almost invariably, the warblers will respond by trying to pry the fingers apart! It's one of our favorite "stupid bird tricks!" Interestingly, this unique, reverse-opening bill action also is shared with orioles.

This photo of an especially colorful SY male American Redstart banded on 6/2 shows an adaptation related to this species' specialized aerial foraging behavior. In all likelihood, the specialized feathers at the base of its bill, called rictal bristles, function like "eyelashes" to keep possibly harmful airborne detritus (e.g., wing scales of moths and butterflies; chitinous appendages of flying beetles and bugs) from getting into its eyes when it makes its mid-air strikes to catch an insect.

Not surprisingly, this effective and important protective adaptation has evolved independently in a number of lineages of "flycatching" birds, including the true flycatchers (see bottom photo in the series of Alder/Willow flycatchers below) and nightjars (like Whip-poor-will).

Speaking of flycatchers, we had an unusual opportunity to compare and contrast two obviously very different "Traill's" Flycatchers banded on 6/1. Although we were a little too busy to measure out the wing formulas of the two birds, which can sometimes help to distinguish the very cryptic Alder and Willow flycatchers (Pyle 1997), the following outwardly visible criteria suggested that we did, in fact, have one of each species in hand. In the series of photos to your left, the presumed Alder is on the bird on the right or in the photo below.

First, the lores of one flycatcher, the putative Alder, definitely were much lighter, and the dorsal plumage of that bird was distinctly greenish. This contrasted with the putative Willow, which was grayer above and did not have conspicuous light-colored lores. The wing bars and tertial edgings of the presumed Alder were perhaps slightly broader and brighter than the bird we believed was a Willow, but this difference was subtle at best.

One trait among those given in Pyle (1997) that did not agree at all with our identification of the two birds, however, was crown spotting: the Alder should have had larger, more distinct crown spots compared to the Willow, but this was not the case (see photo to left bottom; the probable Alder is one on the right).

We banded two second year (SY) American Goldfinches on 6/2. Both were unusually bright and colorful for young birds of their sex. Compare the SY female (top bird in the photo to your left) with what we called an unusually dark ASY female a couple of weeks ago.

The male-like plumage of the SY female would have made for an even more surprising comparison if we'd had a more typical, duller SY male to pose with her.

Last but not least, we banded a new species for the spring season on 6/1--a an adult (ATY) male Pileated Woodpecker. Although we banded a Pileated Woodpecker last spring, too, more often than not we miss catching and banding this species in any given banding year.

When banding volunteer, Mary Shidel returned to the banding lab with her prize, she found a very appreciative audience of 5th graders from the Pittsburgh Urban Christian School (PUCS) on hand to share the occasion.

The day before, Bob Mulvihill had given a program about birds, bird watching, bird research, and bird conservation to the entire group of about 125 students, teachers, and parents of K-5th graders from PUC, who were spending a couple of days at the Ligonier Camp and Conference Center about ten miles away from Powdermill. A follow-up visit to Powdermill was reserved for the older students.

The photos to your left (first photo) show Bob Mulvihill banding the PIWO (the species takes a band size 4), weighing it in the same weighing cone that is used for all other birds banded at Powdermill, including hummingbirds(!)and holding the PIWO up to show visiting 5th grade students, teachers, and parents from PUCS. Puppy, as always, tries to steal a little bit of the show!

Everyone stood back and watched as the PIWO was released out the front door of the lab after banding.

Of course, the Pileated was just one of several birds we had on hand for our visitors from PUCS. In the photo to your left, taken from the outside in (it was a little too crowded "in" for picture taking!), Bob Mulvihill shows the group the waxy red feather appendages that give a Cedar Waxwing its name.

The approaching summer notwithstanding, early morning temperatures on 5/31 were very cool (just under 50°F), and an adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbird caught in a net on the first round of the morning showed the conspicuous signs of hypothermia, or torpor--i.e., fluffed plumage, closed eyes, and a flared gorget (see photos to your left). As we have explained before on this website, male RTHUs can become energetically very stressed, even in summer, because of their very small size. Many, if not most male RTHUs engage in an adaptive lowering of their metabolism (i.e., torpor) overnight in order to conserve energy for the inevitable overnight fast.

The strategy works fine as long as enough stored energy is left to enable the bird to rouse to activity the following morning. If so, then finding food right away becomes a very high priority. Anything that delays or prevents this, such as cold or rainy weather (or getting caught in a mist net), can have serious energetic consequences for male hummingbirds. For the most part, females are spared this energy crisis because they are significantly larger than males, lose less body heat through their proportionately smaller surface area, and have a lower per gram metabolic rate.

For warm-blooded animals, 2.5 grams is something of a physiological threshhold for maintaining homeothermy (i.e., a constant body temperature). It came as no surprise, therefore, when we put this RTHU male on the scale to find that it weighed exactly 2.5 grams. Mulvihill et al. 1992 (A possible relationship between reversed sexual size dimorphism and reduced male survivorship in the Ruby-throated Hummingbird; Condor 94:480-489) showed with an analysis of Powdermill RTHU banding data that males have a significantly lower survival rate and maximum life span (3-4 vs. 7-9 yrs) than females because of their small size.

Fortunately for the torpid male RTHU caught on the morning of 5/31, the energy crisis it faced after being caught in our net was quickly reversible. Give them a number of sips of sugar water, a little time to rev up their metabolism, and males like this one are good to go again!

We banded 272 birds of 42 species during the week and processed 97 recaptures. Our total effort for the week was 1,665 net hours, giving a rather poor capture rate of just 16.2 birds/100 net-hours. It also was our impression that there were few migrants present in the banding area on any given day during the week, due probably to the lack of any weather systems to concentrate and ground them.

Our best day in terms of banding total, species diversity, and capture rate was Tuesday, 5/22, when we banded 70 birds of 27 species at a rate of 19 birds/100 net-hrs. Species contributing most to our total this week were Cedar waxwing (87 banded), American Goldfinch (31), Gray Catbird (19), Indigo Bunting (16) Ruby-throated Hummingbird (13), Common Yellowthroat (12), Northern Waterthrush (8), Swainson's Thrush (8), "Traill's" Flycatcher (7), and five each of Magnolia and Canada Warbler.

Among the 32 visitors who signed our guest book this week were members of the Delaware Nature Society (photo to your left) on a field trip to Powdermill led by Joe Sebastiani (kneeling at right in photo).

We also enjoyed a visit from a group of six interns from Hawk Mountain Sanctuary on 5/25, led by HMS Research Biologist and Intern Coordinator, Lindsay Zemba (photo to your left, standing at left).

In the photo to your left, the six HMS interns from Veracruz, Venezuela, Cambodia, and the U.S. are joined by Molly McDermott (PARC's temporary bander-in-charge; back row, third from right) and two PARC interns from the Dominican Republic, Danilo Mejila (back row, second from right) and Maria Paulino (in front, far left).

The Powdermill banding crew this week was led by Molly McDermott, who is standing in as bander-in-charge during the latter part of the spring and all summer for Adrienne Leppold, who is away supervising a a field crew working on a seabird study for the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

Helping Molly were her spring banding assistant, Pam Ferkett, the Powdermill Bobs (Mulvihill and Leberman), and volunteers Mary Shidel, Lauren Schneider, and Matt Shumar.

As mentioned above, Cedar Waxwings dominated our catch this week. Large flocks remained in the banding area all week, attracted by the flowering trees and shrubs, especially hawthorns and willows, whose flower parts they greedily consume at this time of year. A double-decker net just outside the banding lab accounted for the majority of our waxwing captures. With more than 80 banded, we observed the usual array of waxwing plumage variations, including wholly or partly orange tails (a result of the incorporation into developing tail feathers of rhodoxanthin, a red pigment found in the Tartarian Honeysuckle berries that are frequently consumed during molt, along with normal yellow carotenoid pigments).

This variation is much more frequently seen in the juvenal tail feathers of young waxwings, because their tail feathers are grown in the nest when adults are feeding nestlings extensively on the early ripening (mid-June to July) honeysuckle berries. At Powdermill, at least, these same berries are much less widely available later in the fall when adults are molting their rectrices, and we rarely if ever see orange tipped rectrices in adult birds.

The bird pictured to the left, however, is an adult (ASY) bird, one that must have increasingly fed on honeysuckle berries as the molt of its tail proceeded centrifugally (i.e., from the central tail feathers to the outer ones). The same bird showed another infrequent plumage variation: small wax tips on its tail (especially the yellow central pair) in addition to those present on the tips of its adult secondary wing feathers.

The top photo-pictured bird's tail wax tips were nothing, though, compared to an adult male waxwing banded on 5/26 that had what may well be the most well developed tail wax tips we have ever seen!

The second most commonly banded bird this week after waxwings were American Goldfinches. A little known but useful means for separating SY and ASY goldfinches in spring is the existence of a prealternate molt limit among the greater coverts. The lack of any such partial molt of greater coverts in adult (ASY) goldfinches was first reported by Alex Middleton in his classic study of the molt of this species published in The Condor in 1977 (vol. 79: 440-445).

The photos to the left illustrate this: the top photo is of a SY female that has replaced one inner greater covert (GC 9); the middle photo is an ASY female showing no prealternate molt of greater coverts; the bottom photo is an SY male that has molted three inner coverts (GC 6-8). Although the molt limit is not as conspicuous in the male due to the black color of the retained juvenal GCs, the prealternately molted GCs 6-8 can be seen to be even blacker and far less worn than the adjacent unmolted (juvenal) GCs.

The description of molt in AMGOs in Pyle (1997) is not entirely correct. It states that HY goldfinches molt 4-10 GCs during the first prebasic molt (they do not molt any) and 0 (35%) to six during the 1st PA molt (at Powdermill ca. 90% or more molt at least one GC), and that ca. 30% adults can molt up to two GCs in spring. We have not observed normal PA molt of GCs in any adult AMGOs at Powdermill, although asymmetrical adventitious replacement of GCs sometimes occurs.

We couldn't resist snapping a quick side-by-side photo of two small, mostly yellow, black-capped birds (Wilson's Warbler, left; American Goldfinch, right) banded during the same net round on 5/23.

In our early May highlights we showed a close up picture of dark "gunk" on the tip of the beak of a White-crowned Sparrow. Like the WCSP, the photo of the female American Goldfinch to your left belies this species' fondness for dandelion seeds.

When probing into the unopened seed heads, birds that feed on dandelions in spring encounter the gooey white substance found in the plant's hollow stems, a substance that dries to a rubbery consistency and which apparently is difficult for the birds to clean off from their bills.

We banded just our second Yellow-bellied Flycatcher of the season this week, an SY bird, on 5/24. A more usual spring total by this date would be 20 or more.

Some of you will recall that we consider the YBFL to be literally the "cutest" of the eastern Empidonax flycatchers, because of its comparatively infantile proportions (i.e., disproportionately big head and eyes; small bill and body).

For the same reasons, a Philadelphia Vireo banded on 5/24 looked far cuter than the Red-eyed Vireo caught with it on the same net round.

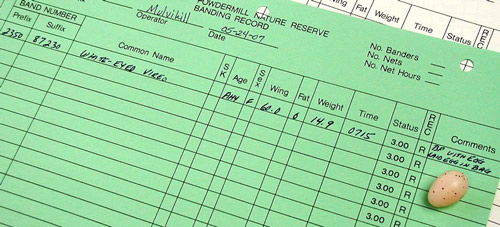

Speaking of vireos, an encounter with another vireo species reminded us on 5/24 of why our banding station protocol encourages examination of the breeding condition of birds at the net and allows for selected birds, e.g., previously banded females with fresh brood patches and/or in gravid condition, to be recorded and released at the net and not brought back to the central banding lab for banding or full processing.

A White-eyed Vireo re-trapped early in the morning on 5/24 was bagged by a less experienced volunteer and returned to the banding lab where it was discovered that she had laid in the bag an egg she undoubtedly was on her way to a nest to lay when she was caught in our mist net. Her elongated, sparsely spotted egg weighed 2.2 grams. Interestingly, the bird still appeared very gravid despite having just laid an egg. And, at 14.9 grams, her weight after having already laid one egg showed that she did indeed have a second very well-formed egg in her oviduct (this notwithstanding the fact that birds lay just one egg a day).

A WEVI with little or no fat and no egg might weigh 11-13 grams. Considering the added weight of the egg that she laid in the bag, this female WEVI must have weighed an amazing 17.1 grams when she was caught in our mist net. The highest body mass recorded in Mulvihill et al. (2004, Relationships among body mass, fat, wing length, age, and sex for 170 species of birds banded at Powdermill Nature Reserve, EBBA Monograph No. 1) based on 685 WEVI banding records is 16.8 grams, and this was for a bird with maximum fat deposits.

What is undoubtedly one of the last Lincoln's Sparrows of the spring season was banded on 5/24. The LISP is a especially finely marked bird whose neatly tailored appearance rarely comes across well in field guide illustrations or photographs.

The photo to your left is our latest attempt, and we think it's a bit closer to doing justice to the understated beauty of this bird than any we've taken before.

We observed a couple of unusual cases of eccentric wing molt this week: an SY female Scarlet Tanager banded on 5/23 (top photo to your left) had replaced (presumably during her first prealternate molt) three outer primaries (note the darker gray color and blacker shafts) and four inner secondaries on both wings (as well as all of her rectrices); on 5/27.

We banded an SY female Indigo Bunting (bottom photo to your left) that appeared to have undergone a very nearly complete first prebasic molt including all but the innermost (juvenal) primary and several inner primary coverts.

On 5/22, we banded this unusually dull SY male Canada Warbler that had just a trace of a black "necklace."

Female Black-throated Blue Warblers arguably are among the most confusing fall and spring warblers. But many of them are substantially less well marked than this SY female banded on 5/24, with her very prominent white wing spot and eye markings.

It has been a good spring flight of Mourning Warblers at Powdermill. This ASY male and SY female banded on 5/26 brought our spring total to 21 (our long-term spring average is 14).

It's also been a very good spring migration for Indigo Buntings (51 banded through 5/27 compares with a long-term spring average of about 30). We couldn't resist taking yet another photo of a brilliant ASY male, this one banded on 5/26.

On the last banding day of the week, we caught what surely is the quintessential blue bird: an ASY male Eastern Bluebird.

Of four new species banded for the season during the period, three were flycatchers, including this Eastern Wood Pewee. The other flycatchers were Yellow-bellied and Acadian.

We enjoyed a visit from Greg Baruffi, a MAPS bander from Winchester, VA. Greg is pictured here handling our fourth Spotted Sandpiper of the season, a SY female. Spotted Sandpipers can be sexed by a combination of bill and wing measurements (females are larger than males) and by the amount of spotting on their under parts (females are more heavily spotted than males).

Spotted Sandpipers can sometimes be aged SY if they have retained juvenal flight feathers. In the bottom photo to your left, notice the retained inner three primary coverts and primary 1.

After a long winter, one of the pleasures of spring banding is the colorful parade of Neotropical migrants, especially the brilliantly plumaged adult males of many species, like the Indigo Bunting (top photo to your left), Scarlet Tanager (middle photo to your left) and Northern Parula (bottom photo to your left) banded at the end of the week.

Come to think of it, some of the SY males vied with adults of their species for most brightly colored plumage!

Notice that while this Magnolia Warbler's plumage is very striking, it has the trademark brownish retained juvenal primary coverts and alula of an SY bird.

According to Dunn and Garrett (Peterson Field Guide to Warblers), a conspicuous reddish orange crown is typical of Yellow Warblers belonging to the "Golden" subspecies group, which is distributed across southern Florida and the Caribbean.

However, this plumage characteristic is only occasionally observed in adult males of Northern subspecies like those banded at Powdermill. This ASY male Yellow Warbler banded on May 17th had much more extensive color in its crown than we usually see.

This ASY American Goldfinch banded on May 20th had unusually dark pigmentation on the wing and tail for a female. That combined with her broad, very truncate tail feathers supported the age determination.

We banded our first Philadelphia Vireo on 5/15, and the flight continued with 4 more banded during this time period. We are already approaching our long-term spring average for this species (~9), but the greatest spring flight occurred in 1990 when 56 were banded during a gypsy moth outbreak.

Countless thousands of early instar larvae were gleaned by PHVIs and other insectivorous songbirds from the leaves of willows and other shrubs next to the net lanes.

We logged 1,845 net hours of effort during these four days and banded a total of 319 birds of 51 species, which is excellent species diversity for our site. In addition, we recaptured 151 previously banded birds. Our best day was 5/17 when we banded 171 birds of 40 species (capture rate of 27.4 birds/100 net-hours) and processed an additional 55 recaptures.

Top ten species banded were American Goldfinch (40 banded), Cedar Waxwing (37), Magnolia Warbler (30), Red-eyed Vireo (19), Ruby-throated Hunmmingbird (16), Swainson's Thrush (14), Rose-breasted Grosbeak (13), Indigo Bunting (9), and American Redstart (8). Thanks to fellow banders Greg Baruffi (VA), Keith McKenrick (Northern PA), Joe Schreiber (MD) for paying us a working visit this week, to Powdermill staffers Mary Shidel, Pam Ferkett, and Kristin Sesser, and to volunteer Brent Worls for their assistance this week.