October - November 7, 2014

The month of October had the highest capture number of the fall banding season with 3,495 newly-banded birds. We also had our 3rd biggest day ever on October 23rd when we caught a total of 602 birds. Things began to slow down as migration came to an end in November, but overall, this fall was one of the most successful (and fun!) seasons at PARC.

Throughout the entire Fall season (from August 1st to November 7th), we banded 7,139 birds and collected data on another 2,802 recaptures across 108 species.

Photo highlights for the late fall include: Northern Flicker; Yellow (Eastern) Palm Warbler; Marsh Wren; Savannah Sparrow; Northern Saw-whet Owl; White-crowned Sparrow (Gambel’s and Eastern races); Eastern Bluebird; and Mallard. Highlights also include late migrants, and birds with unusually colored plumage.

We caught just 12 Northern Flickers this fall, including this female hatch-year, photographed on October 4th.

Males and females of this species can be distinguished by the presence of a malar stripe – or ‘mustache’. Females tend not to have any colored feathers in this area, while males have a very prominent mustache. The western red-shafted race have red malar stripes while the eastern yellow-shafted race have black malar stripes.

Northern Flickers, like all woodpeckers, use their incredibly stiff tail feathers (called retrices) to stabilize themselves on trees while foraging.

The tail feathers and undertail coverts (shown here) of Northern Flickers exhibit an amazingly complex and beautiful pattern.

One measurement bird banders take as they collect data or "process" a bird is the 'fat score'. Fat scores are a visual estimation of the amount of fat located in the furcular hollow. The furcular hollow is located at the top of the breast just above the clavicles. The fat appears yellow or pinkish yellow and can be seen under the bird's translucent skin. Thus, we are able to see the fat by gently blowing the feathers apart as seen here.

Fat scores tell us about a bird’s energetic condition and readiness to migrate. The amount of ‘fuel’ it has stored in preparation for flying will determine how many hours at a time it can fly without needing to stop to eat. Some birds, like this young Connecticut Warbler we caught on October 4th, are EXTREMELY fat and can to fly hundreds of miles in a single night.

We score a bird’s fat in one of four categories. To put it simply, we say 0 for no fat visible, 1 for some, 2 for a good store, and 3 for a lot. Birds that have a score of 3, like this hatch-year Tennessee Warbler (photographed on October 5th) are sometimes called butterballs—can you see why?

This young bird will have no problem making the first leg of its long flight toward its wintering habitat in Central America, Columbia, Venezuela, or Ecuador.

On October 8th we recaptured this adult female Eastern Towhee. She was originally banded on May 5th, 2012 and aged as an After-Second Year bird. That means that at the time of her capture this fall, she was at least 5 years old.

But we told her she didn’t look a day over 3.

These two adult Purple Finches, caught on October 10th, are a good example of sexual dimorphism, an evolutionary trait resulting from natural selection.

More brightly-plumaged males are more attractive to females. It takes energy to produce rich colors and shows a high level of fitness and health – both good qualities in a potential mate. The downside to this flashiness is that it also makes males more susceptible to predation, therefore they frequently do not live as long as females.

In nature however, your "fitness" ultimately depends on your ability to pass on your genetic traits, so in the end, attracting a mate outweighs living a long life.

A Male (left) and a female (right) Purple Finch.

On October 11th, we had our first truly big day of fall banding, when we caught over 300 birds.

This after second-year Cedar Waxwing was the 300th bird of the day.

Can you spot the waxy tips to the wing feathers?

In the fall, we also spend a few nights (…late nights) catching Northern Saw-whet owls, one of the least commonly seen birds in North America.

This season we were able to catch 8 individuals; 7 unbanded birds, and 1 recapture. This recap was banded the previous year in the Allegheny Mountains of eastern West Virginia.

Molt limits in Northern Saw-whets can be seen in normal lighting, but another useful and beautiful way to age these birds is by looking at their wings under UV lights. The flight feathers of Saw-whet Owls contain porphyrins, a compound that is fluorescent under UV light.

Since porphyrins fade over time, older feathers will glow less brightly than replaced ones and different generations of feathers are therefore distinguishable.

This individual has 2 generations of feathers making it a Second-Year bird.

Savannah Sparrows are another uncommon capture for us. This season we caught two individuals on October 22nd, both of them hatch-year birds.

The short tail, smallish head, and distinctive yellow spot before the eye make this sparrow distinguishable from others in the Emberizidae family.

Here is a great comparison of four sparrow species. From left to right: Chipping Sparrow, Savannah Sparrow, Field Sparrow, and Swamp Sparrow.

Note the rufus crown and dark eye line of the Chipping Sparrow; the yellow lores, brown underparts and black streaks on the breast and flanks of the Savannah Sparrow; the pink bill and unstreaked, buffy breast of the Field Sparrow; and the ‘muddy’ brown flanks and throat, dark eye line, and gray face of the Swamp Sparrow.

October 23rd was perhaps the most exciting day here at Powdermill this fall, when we caught a total of 602 birds (of which 537 were unbanded). It was the third highest capture number for a single day of banding in PARC’s history.

Birds were everywhere!

We are extremely thankful for the help of our volunteers that day. We would not have been able to band so many birds and collect so much quality data with such efficiency if not for each and every one of them.

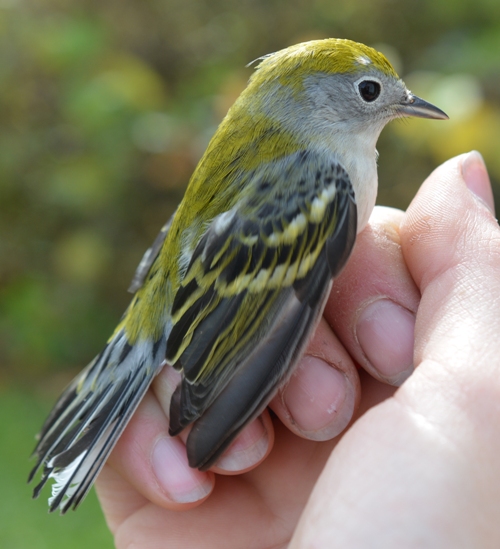

A total of 51 Palm warblers were caught this fall. Of that number, 49 were of the Western form that breeds in the western part of the species’ range (pictured here).

And 2 were Yellow Palm Warbler which breed in the eastern part of the species’ range. Since the eastern portion is almost coastal they are far rarer in this area. Since 2010, only 6 individuals have been caught, including the two hatch-year males we caught this fall on October 11th.

Yellow Palm Warblers (like this one) differ from their Western counterparts in the vibrancy of their coloration; they are brighter in color overall, and entirely yellow underneath, while Western Palm Warblers are duller in color, with whitish bellies.

Wrens are always a nice treat (though they are quite the escape artists…).

Pictured here is an adult House Wren.

House wrens may look similar to Winter Wrens, but they are duller in color, have longer tails, and the barring on their flanks does not go past their legs.

Winter Wrens (or “little balls of squirm" …note the blurry photo of this hatch-year caught on October 18th) are warmer (redder) in color, have noticeably short tails, and more extensive barring on their side and belly.

They are one of the smallest birds we catch, and yet they are capable of singing with 10 times more power than a crowing rooster (per unit weight).

Less common among the wrens caught at Powdermill are Marsh Wrens. We caught 4 individuals this fall, two in September, and two in October. That’s about twice the average of the last several years!

Unlike many birds, male Marsh Wrens will sing on their breeding grounds not only throughout the day, but also throughout the night.

Pictured here is an adult White-crowned Sparrow.

There are five subspecies of White-crowned Sparrows in North American, and one of the best ways to distinguish between the two races that migrate through Southwestern Pennsylvania is to pay attention to the amount of black or grey on the bird’s lores (the area in front of the eye).

We caught both races here at Powdermill this fall, the Eastern White-crowned Sparrow (pictured here, an adult caught on October 29th, one of 28 for the fall), whose black crown stripe extends down onto the lores and in front of the eye, cutting short its white supercilium...

...and the western race, called ‘Gambel’s’ White-crowned Sparrow (pictured here, an adult caught on October 28th, one of only 8 Gambel’s this fall), whose white eye stripe is not cut short by black in front of the eye.

Though subtle, the bill of the Gambel’s race is also more yellow and less pink than its Eastern counterpart.

A bird’s diet can affect the color of its feathers. A great example of this is the brightly colored tip of a Waxwing’s tail.

Usually, it is yellow, but it can also be orange (or both!). The orange coloration didn't appear in waxwings until the Eurasian honeysuckle bush was introduced to the U.S in the 1950s. Since then, the berries have become a favorite food source for Cedar Waxwings and other species.

Honeysuckle berries contain carotenoids – chemicals (or pigments) that reflect red wavelengths and result in red, yellow, or orange coloration when stored in feathers. The more honeysuckle berries a bird eats, the more red carotenoids will be contained in its feathers, and the more orange those feathers will appear.

Pictured are the typical Waxwing tail (above, yellow tips), a tail grown while consuming a lot of red carotenoid-containing fruit (at left), and...

...a tail with a mixture of both orange and yellow. This bird had to replace some tail feathers (perhaps caught on a branch or pulled out by a predator) and the replaced feathers (yellow-tipped) were grown at a time when the bird's diet was more varied, including less of the honeysuckle berries.

We saw some very fascinating differences in plumage coloration this fall in several species, including this young Chestnut-sided Warbler caught on September 9th.

In the fall, the back, nape, and crown are normally yellow-green in this species, and do not have the orange tinge that this young bird’s plumage exhibited.

This adult White-throated Sparrow displayed the same dietary-induced orange coloration in its lores.

In White-throated sparrows, the lores are usually a bright yellow, as they are in the individual pictured here on the left.

And yet another example can be found in the pink-toned plumage of this hatch-year Hermit Thrush. We caught this bird several times, and came to recognize it by its unusually pink belly.

Hermit Thrushes normally have pale undersides, without the blush of color this bird had.

"Pinky" visited the banding lab several times throughout October and November.

Here is another example of unusual plumage, this time in a hatch-year Eastern Towhee, caught on October 12th (left).

This bird demonstrated an uncommon amount of rusty-brown throughout its body plumage (note the difference between these two birds, though both are hatch-year males of the same species).

Brown coloration in birds is the result of another pigment, called porphyrin, which is produced by modifications to amino acids within the bird’s feathers.

Flight tunnel technician and BirdSafe Pittsburgh Coordinator Matt Webb and Seasonal Banding Assistant Kittie Yang, marveling at the difference in plumage between the two young birds.

At the end of October, we had a few surprise warblers in our nets. These birds were late migrants, the last of their kind passing through on their way South.

Among them was this adult female Chestnut-sided Warbler, whom we caught several times.

This adult male Black-throated Green Warbler, caught on October 31st, was the latest of his kind to be captured in PARC’s history (the prior record was October 26th, 1975).

On November 6th, we caught a species that is extremely common, but not an extremely common catch in a mist net: a Mallard.

Here’s a nice close up of this bird’s violet-blue, iridescent “speculum” patch of feathers.

Most waterfowl species have these distinctly colored wing patches, and they are a helpful key in identification.

The webbed foot of this female Mallard helps her swim at surprisingly fast speeds.

Back with her comrades.