August - September 2014

Fall banding began August 1st and lasted through November 7th. The top ten species for the fall include: Yellow-rumped Warbler (625), Cedar Waxwing (513), American Goldfinch (452), Magnolia Warbler (340), Gary Catbird (327), White-throated Sparrow (309), Ruby-Crowned Kinglet (267), Purple Finch (263), Swainson’s Thrush (262), and Ruby-throated Hummingbird (245).

With such a large diversity of beautiful and fascinating species to highlight, we’ve separated the season into two sections: early and late Fall.

August kick-started the early part of the season with some great catches, including two Olive-sided Flycatchers, a Sora, and the first wave of gorgeous warblers passing through on their way South. The month of September had the greatest diversity of birds captured, with a total of 86 different species.

Uncommon species caught in the early fall included: Olive-sided Flycatcher; Sora; Lawrence’s Warbler; Yellow-throated Vireo; Sharp-shinned Hawk; Solitary Sandpiper; Yellow Warbler; Chimney Swift; Pileated Woodpecker; and American Woodcock.

Only two Olive-sided flycatchers were caught this fall, the first a handsome hatch-year caught on August 27th (left), the other a hatch-year caught on the 29th

They are easily identified from other flycatchers by their larger size, somewhat short tails, and ‘vested’ appearance from a white chest that contrasts with dark gray sides.

Olive-sided Flycatchers are a rare capture for us. In fact, the species is in decline throughout its range, likely due to the loss of its wintering habitat. They are listed on the 2014 State of the Birds Watch List.

This hatch-year Sora, photographed on August 28th, was the only one caught this year. A capture rate of one per year has been the standard at Powdermill since 2012, so this bird was a fun catch.

Soras are precocial, meaning that they hatch advanced enough in their development to feed themselves almost immediately. A just-hatched bird can walk and even swim short distances within just a few hours! Four weeks after hatching, they are completely independent.

Wilson’s Warblers, named after the Father of American Ornithology, Alexander Wilson, are one of the easiest warblers to get eyes on. They are not fearful of humans, and remain visible as they forage on the edges of brush and leafy branches, catching insects mid-air. This after-hatch-year male was banded on August 28th.

Like other birds that specialize in catching insects while in flight, Wilson’s Warbler have rictal bristles – thin, particularly stiff feathers that protrude from the beak. These small bristles help funnel insects toward the mouth, protect the birds eyes as it catches them, and may even act much like whiskers, providing tactile and sensory feedback.

American Goldfinches took 3rd in the top ten species we caught this fall, and we were able to get some great comparison shots.

Pictured here are the wings of a hatch-year male (above) and a hatch-year female (below). Notice the depth and darkness of the black on the male’s wing, compared to the duller, browner coloration of the female’s wing.

The same difference can be seen in their tails, where the female’s is again more brown (left) as opposed to the male’s which is blacker (right).

The banding lab caught 12 Bay-breasted Warblers this fall, all in the month of September.

Pictured here is a hatch-year male from September 2nd.

Bay-breasted warblers in non-breeding plumage may easily be confused with Blackpoll Warblers in non-breeding plumage. But note that the Blackpoll

(at left, photographed on September 30th) does not have buffy or rufus coloration on its sides, has streaking on its underparts, and has a more defined eyestripe. Blackpolls also have paler legs and feet.

Pay attention, too, to the undertail coverts of both birds (helpful for identification when they are in the tree branches overhead!)—the undertail coverts of the Blackpoll Warbler (on the right in the adjacent photo) are white, while the undertail coverts of the Bay-breasted Warbler are buffy.

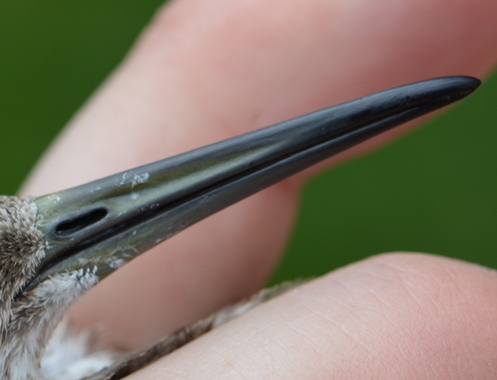

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds were our 10th most captured species this fall.

Pictured here is a hatch-year female caught and banded on September 5th.

Since the male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds do not get their red feathers on the throat until later in the year, we cannot determine the sex of this bird based on plumage alone. However, Hummingbirds can also be sexed by wing chord, since female wings are generally longer than male wings; we were able to identify this individual as female using this measurement.

When determining the age of hummingbirds, we also take a close look at their bills; this is because young birds have striations, or little corrugations, on the upper mandible’s edge. These will disappear as the bird ages and as its bills becomes smoother and harder. The scalloped rufous edging on the feathers of the head seen here is also characteristic of young Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

This gorgeous after hatch-year female Blue-winged Warbler (one of 19 for the fall) was caught on September 9th.

Blue-winged Warbler populations have been expanding their range northward, interbreeding with Golden-winged Warblers – one cause of their Golden-winged cousin's decline in recent years.

And on that note, perhaps one of the most note-worthy highlights of banding this fall was capturing not just one, but two hybrid Lawrence’s Warblers, one adult male (right) and one juvenile female (left), on September 16th.

Since 1961, the banding lab has caught only a total of 10 Lawrence’s warblers. These two were the first since 2006!

Blue winged and Golden-winged warblers hybridize into two forms – “Brewster’s” and “Lawrence’s.” Brewster’s are the more common hybrid, the result of a breeding pair of one pure Golden-winged and one pure Blue-winged warbler.

The Lawrence’s is far rarer and is the result of a breeding pair of either two hybrid adults, or a backcross of a hybrid with a pure adult.

Pictured at left: adult male Lawrence's Warbler, exhibiting the recessive plumage patterns of both the Golden-winged and Blue-winged warbler species.

Hatch-year female Lawrence's Warbler.

Here is a nice comparison shot of three Hooded Warblers, caught on September 9th.

From left to right: a hatch-year male, an adult male, and a hatch year female.

Notice the difference in the amount of black on the cap and throat (or ‘hood’) of each bird.

Speaking of Hooded Warblers, on September 14th we caught this hatch-year male, whose molt pattern was unique.

Normally by mid-September, hatch-years of this species have replaced all of their juvenal feathers within the greater coverts; this bird had retained four of his.

The feathers highlighted here are those grown by the bird while it was still in the nest. They are browner in color and, when viewed closely, are of poorer quality than the surrounding feathers that have already been replaced.

Yellow-throated Vireos are the most bright and colorful of the Vireonidae family, and they are another uncommon capture for us.

This hatch-year caught on the 14th of September was the only one to be caught and banded this fall.

A hawk in a mist net is one of the most exciting things a songbird bander can see. This hatch-year female Sharp-shinned hawk was one of just 3 caught this fall.

Like most hawks, this species is one of the easiest to age; immature birds (like this one) will be mostly brown and have vertical streaking on the chest. An adult will have a slate colored, blue-gray back and cap, with horizontal red-orange streaking across the chest.

Sharp-shins are the smallest member of the Accipiter genus.

As they age, their eyes will gradually turn from yellow - like this young female’s - to a deep, ruby red; another characteristic used in aging.

The protruding ridge on the brow of many raptor species acts as a shield to protect their eyes from the glaring rays of the sun while hunting.

One of the 3 Solitary Sandpipers for the fall, caught on September 19th. Solitary Sandpipers occasionally stop at our ponds for a few days on their way south.

They are one of only two species of the world’s 85 sandpipers that lay their eggs in tree nests rather than on the ground; they don't build their own, but use those of the American Robin, Rusty Blackbird, Eastern Kingbird, or Cedar Waxwing.

Sandpipers are truly extraordinary birds. The tips of their bills have special cells (called ‘corpuscles of Herbst’) which sense differences in the tiny pressure waves created by their bills when they stick them in the ground.

Since larger objects will send back different pressure waves than will grains of sand or dirt, sandpipers are able to sense within just a few seconds when differently sized objects (say, a shellfish of some kind) are present in the ground.

Foraging is a snap.

While they are a common catch in the Spring, Yellow Warblers are more rare in the fall because they are one of the first species to leave our area; it is not uncommon for these birds to start their southbound flight in July.

This adult female, caught on September 20th, was one of just two for the season and could easily have come from as far away as Alaska!

Another very exceptional capture was this hatch-year Chimney Swift, banded on the 21st of September.

Since they don’t often come low enough to get caught in mist nets, only three individuals have been caught in the last several years.

Chimney swifts spend most of their life in flight (note the long, powerful, slender wings of this acrobatic flyer, left), never landing in trees. In fact, they cannot perch, and only ever cling to the sides of vertical surfaces.

Chimney swifts are aptly named—the species increased in number as chimneys became more popular in North America. They roost together in chimneys for warmth and, amazingly, the temperature inside a chimney where a group is roosting can be up to 70 degrees warmer than the outside temperature!

American Woodcocks are not very common captures, either; we had just three this fall, including this hatch year caught on September 25th.

Woodcocks are a good example of “cryptic” coloration—coloration that allows a species to thoroughly blend in with its surroundings and remain unseen.

Woodcocks spend most of the time on the ground using their long beaks to forage for earthworms; thanks to their plumage, they are well camouflaged among the leaves.

Here is another amazing bird we caught on September 27th: a Grasshopper Sparrow. The last time the banding lab caught one of this species was in the summer of 2012, and before that, not since 2007.

The most Grasshopper Sparrows captured in a single year was 9 individuals, in 1963; the average for the last several decades has been just 1 (if that) each year.

At first glance, this sparrow may look like an ordinary brown bird, but look closely, and you will see a beautiful spectrum of cinnamon, rust, yellow, and ivory shades.

Before this fall, only 34 Pileated Woodpeckers had been caught at Powdermill since the banding station began in 1962.

We were fortunate enough to catch the 35th on September 29th – this striking hatch-year Male.

Pileated woodpeckers use their powerful, chisel-like bills to excavate large nest holes (which are oblong, rather than circular – a key you can use to identify their cavities) in dead trees.

Their cavities are not just useful to the woodpeckers; they also provide vital refuges for other species - swifts, owls, bats, pine martens, and ducks, among them.

This hatch-year Orange-crowned warbler, caught on September 27th, was one of 7 for the fall.

When you first see this species, you might think, “Orange-crowned Warbler, you say? But I see no orange crown...”

It’s true, it is rarely possible to see the orange feathers on the tops of their heads (especially if you are looking up at them in a tree…), but believe us, it exists!

Young Tennessee Warblers (like the one pictured at left, caught on October 8th) can look quite a lot like Orange-Crowned Warblers. But some difference can help us ID the two species.

Tennessee Warblers lack the more distinct yellow or white eye-arcs and the olive-yellow smudged streaks on the flanks that the above Orange-crowned Warbler possesses.

The undertail coverts are probably the most helpful characteristic; in the Orange-crowned warbler, they are a bright yellow and often the most colorful part of the bird, whereas in the Tennessee Warbler they are white or pale yellow, and are dull in comparison to the rest of the plumage.

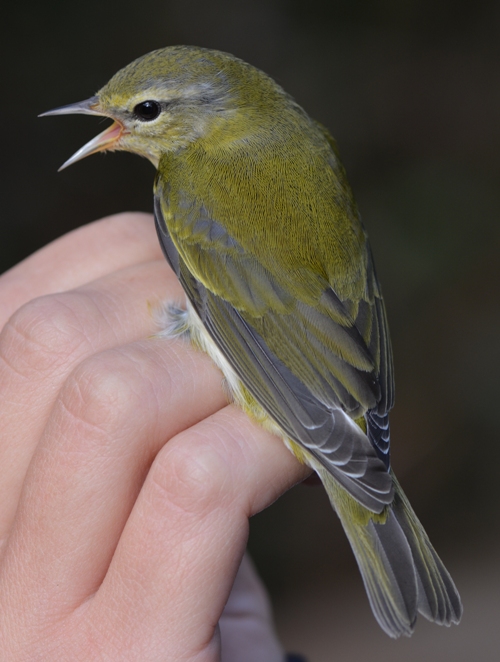

There are several characteristics we use to age birds, and not all of them involve molt limits and replaced feathers.

For some birds, we look at the color of their mouth lining. This is because young birds can retain some of the yellow or pink coloring they had as nestlings (which in the nest, acts as a kind of target for their parents when the nestlings open their mouths to beg for food). A bird’s mouth lining darkens as it ages.

Pictured here is an adult Blue Jay, caught on September 27th.

This bird's dark mouth lining confirms that it is an adult.

This hatch-year Gray Catbird, on the other hand, still has quite a bit of yellow/pink coloration.

In some species eye color is also helpful in aging. Eastern Towhees, for example, have light to reddish-brown eyes when hatched, which become redder as they age.

The very red eye of this male Towhee, banded on September 27th, indicates clearly that it is an adult.

From September 8th-12th Powdermill held an Advanced Bird Banding Workshop, during which participants from all over North America spent the week extracting, banding, and processing hundreds of birds while learning techniques in the aging and sexing of many different species.

Workshoppers enjoyed the diversity and beauty of birds passing through the banding lab, and Powdermill’s staff had a great time sharing their wealth of knowledge with them!

Pictured here are participants examing a Gray Catbird and an Ovenbird, as they learn to look for molt limits and other important characteristics.

Pictured here are workshop participants, along with PARC volunteers (whose help during the workshop was greatly appreciated!) Gigi Gerben (second from left), Jim Bernat and Debbie Ball (front left, squatting), and NABC trainer and former PARC staff member Annie Crary (kneeling, center).

Also pictured are PARC staff members Mary Shidel (top of sign), Matt Webb (hiding… can you find him?), Banding Coordinator Luke DeGroote (front, elegantly sprawled), Kittie Yang (doing an impressive split), Bo D’Amato (third from right), Katie Barnes (second from right) and Margaret Rohde (far right).

Over the weekend of September 12th-14th Powdermill also hosted a certification session, during which individuals were rigorously evaluated by The North American Banding Council (NABC) in order to attain certification in one of three levels: Assistant Bander, Bander, or Trainer.

Here, NABC trainer Adrienne Leppold examines a band placed on a Northern Waterthrush.

NABC trainer Dan Small looks on as a workshop participant determines the age and sex of a Chestnut-sided Warbler.

Trainers David Holmes and Adrienne Leppold (right) watch while another participant consults Pyle, the bird bander’s guide for identifying, aging and sexing passerines and other birds.

Pictured here with PARC staff are NABC trainers (standing, left of sign) Andrea Paterson, David Homes, and former Powdermill Banding Coordinator Robert Mulvihill, former staff member Annie Crary (kneeling, left of sign), and Dan Small and Maren Gimpel (kneeling, front of sign).

Also pictured are PARC volunteers Laura-Marie Koitsch (third from right) and Liz Abraham (seated, far right), a visiting graduate student from Youngstown State.

We were also very honored to have Bob Leberman (second row, third from left), the founder of our banding program, present for the certification.

September 19th is one of the most important days here at the Avian Research Center. Why? Because it’s International Talk Like a Pirate Day.

And as you can see, PARC staff and volunteers take it very, very seriously.

That's it for the first part of our fall highlights - check out all the great catches we had in October and November by clicking on the link to our Late Fall Pictorial Highlights!