August - September 2009

Belted Kingfisher flying over Powdermill

The bird banding lab was renovated in 2009 which included new displays, a pulley system to hold bird bags, a computer to allow for direct entry of the banding data, and, later in the year, we will be installing video equipment to upload banding demonstrations to the internet. Pictured below are banded birds hanging from carabineers attached to the pulley setup.

In August we captured 2 Great-crested Flycatchers, a species seldom captured at Powdermill despite being a breeding bird on the reserve. The GCFL is a member of the group of Myarchus flycatchers that all look very similar and reach their greatest diversity in Latin America. However, they represent the only species of this genus in eastern North America. The bird pictured below was identified as a HY bird by the molt limit among its median and greater coverts.

On September 26th, a flock of about 25 birds (mainly warblers, and a few vireos) were caught in a single net.

One of the most exciting birds banded at Powdermill this fall was a Prairie Warbler (left) with a vibrant orange face and breast. Prairie Warblers usually show an entirely yellow and black face pattern (right). This plumage variation occurs infrequently among bird species and is due to consuming large amounts of berries from Morrow's and Tartarian honeysuckle during feather growth. This is more commonly seen in juvenile Cedar Waxwings, but also has been found in Yellow-breasted Chats, and Kentucky Warblers.

In the fall, a few species of warblers can be easily confused. One of the best known cases of this is differentiating between the Blackpoll and Bay-breasted Warblers. As shown in the photographs, the face patterns of these two species can be incredibly similar.

In fall plumage, the Blackpoll (left) and Bay-breasted (right) Warblers can look very similar. However, once in the hand, they are relatively easy to distinguish the two species. Bay-breasted Warblers often have some bay color on their flanks, are slightly larger, and gray feet (rather than yellow for Blackpoll).

Below shows the plumage variation between sexes of Black-throated Blue Warblers and Hooded Warblers.

The female Black-throated blue Warbler's (bottom) plumage is more drab overall and helps the bird better camouflage itself throughout the nesting period. The male's (top) plumage is much more striking which aids mate attraction.

However, in a number of species, older females become more colorful and begin to resemble males.

This occurs with Hooded Warblers where old females occasionally display a full black hood. The Hooded Warblers shown below are of an AHY male (top)and an AHY female (bottom). The HY female Hooded Warbler typically has no (or very little) black on the crown or throat.

The Cape May Warbler is another species that shows a lot of plumage variation during fall migration. Pictured below is a drab HY female (left) and a more colorful HY male (right). Although birders sometimes find this species hard to identify during fall migration, all plumages include streaking on the breast, and its Latin name (Dendroica tigrina) is derived from this characteristic.

Plumage variation between age classes in male Rose-breasted Grosbeaks can be seen here. The photo in the middle shows a HY male (left) and an AHY male (right). Notice the difference in coloration (especially as it pertains to the amount of black in the wing) and the size of the white patch on the wing of the two age classes.

The photo on the top is of a HY male (notice the molt limit among its greater coverts) and the photo on the bottom is a closer look at the AHY bird.

The Golden-winged Warbler is an exciting bird to capture at Powdermill. The brightly colored male (top) and the grayish female (middle) are beautiful to see up close, but are also of conservation concern because of, among other factors, the expansion of the Blue-winged Warbler (bottom) into its breeding range (and subsequent hybridization).

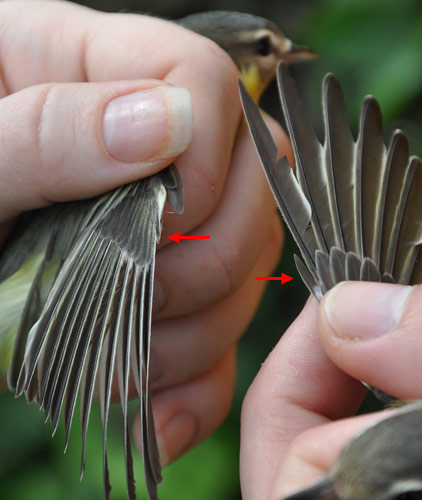

A Philadelphia Vireo (left) and a Warbling Vireo (right) are shown together. These two species have extremely similar plumages and are best identified using a number of criteria, including plumage aspect (extent of yellow-wash on the underside which is often, but not always, more extensive in the Philadelphia Vireo), bill size (generally larger in the Warbling Vireo), and, perhaps most definitively, the length of the vestigial tenth primary (2nd picture), which is markedly longer in the Warbling Vireo (longer than primary coverts) than in the Philadelphia Vireo (shorter than primary coverts).

Much of the literature also describes a darker loral area in the Philadelphia Vireo versus the Warbling Vireo, but as can be seen in the photos below, overlap exists and this criterion should therefore be used with caution.

Philadelphia Vireo

Warbling Vireo

Each fall we capture a handful of the 'skulking' Oporornis warblers - birds that generally forage on or close to the ground, making them a difficult target for birders. A Connecticut Warbler (top) and a Mourning Warbler (bottom) are shown to the left. Both photos are of adult males.

A unique feature (among many!) of birds is the ability to move the upper bill relative to the skull, which is called cranial kinesis. In species such as the American Woodcock, this allows the bird to easily grasp subterranean prey items while the bill is plunged into the ground.

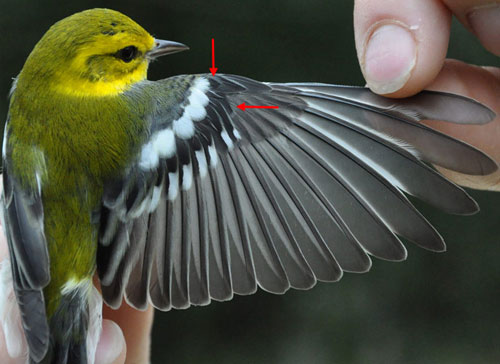

This fall an advanced banding workshop was offered at Powdermill for banders to gain a better understanding the use of molt limits to determine age in birds. For most species, the age of a bird can be identified by determining whether a molt limit exists between retained juvenile feathers and those replaced during the first pre-basic molt.

The Eastern Phoebe wing pictured below shows a molt limit in the greater coverts (two outer retained feathers) as well as a replaced CC (carpal covert)and A1 adjacent to the retained A2 and A3 feathers. Note the difference in shaft and overall color between the two generation of feathers - the older, retained juvenal feathers are of poorer quality and are thus browner and less lustrous than the formative, replaced feathers. This pattern indicates that this is a hatch-year bird.

These Black-throated Green Warblers also illustrate the different molt strategies found in after-hatch-year versus hatch-year birds. An A1 molt limit (somewhat difficult to see in the photo) is seen in the hatch year bird (top) - this incomplete molt strategy (replaced A1 but retained A2, A3, and primary coverts) allows banders to age many species throughout the year. An absence of any molt limit can be seen in the adult wing (bottom), reflecting the complete feather replacement strategy found in most adults.

Fall 2009 banding staff:

Andrew Vitz, Mary Shidel,

Jeff Moker, Tara McAllister,

Alice Van Zoeren, Bob Leberman

Visiting banders and volunteers:

David Hodkinson, Ian Ausprey,

Marja Bakermans (and Boden Vitz), Bob Vitz,

Marcia Arland, Janet Van Zoeren.

Not pictured: Ellen McCallie, Cokie Lindsay, Jeff Territo, Molly McDermott, Annie Lindsay, Julie Zeyzus, and Mack Frantz.