August 1 - November 5, 2017

During the Fall of 2017 we captured 9,341 birds (6,602 new birds and 2,739 recaps). Leading the top-ten list of newly-banded birds (by a wide margin) were Swaison's Thrushes (pictured)-- we banded 608 birds of this species, well above our 56-year average of 229.

The rest of the top-ten species were: Magnolia Warbler (495), Ruby-crowned Kinglet (446), American Goldfinch (388), Song Sparrow (280), Gray Catbird (274), Ruby-throated Hummingbird (243), and Red-eyed Vireo (211); American Redstart and Common Yellowthroat were tied for tenth place with 208.

Although not in our top-ten list, Black-throated Green Warblers were present in near-record numbers this year; we banded 154 (avg=62). Their abundance afforded us an opportunity to take photographs across all ages and both sexes (pictured). As with most warblers, the males of this species are brighter with more striking plumage characteristics.

We are often asked how we can determine the age of a bird. Most birds will molt (replace) at least some of their feathers after they leave the nest and before migration, resulting in two generations of feathers. Feathers grown in the nest are of a lesser quality because the bird is quickly growing ALL feathers at once. Feathers molted after fledging are replaced sequentially and usually the bird is only replacing some wing coverts and body feathers, resulting in feathers of a higher quality (better sheen, more intense color, structurally stronger).

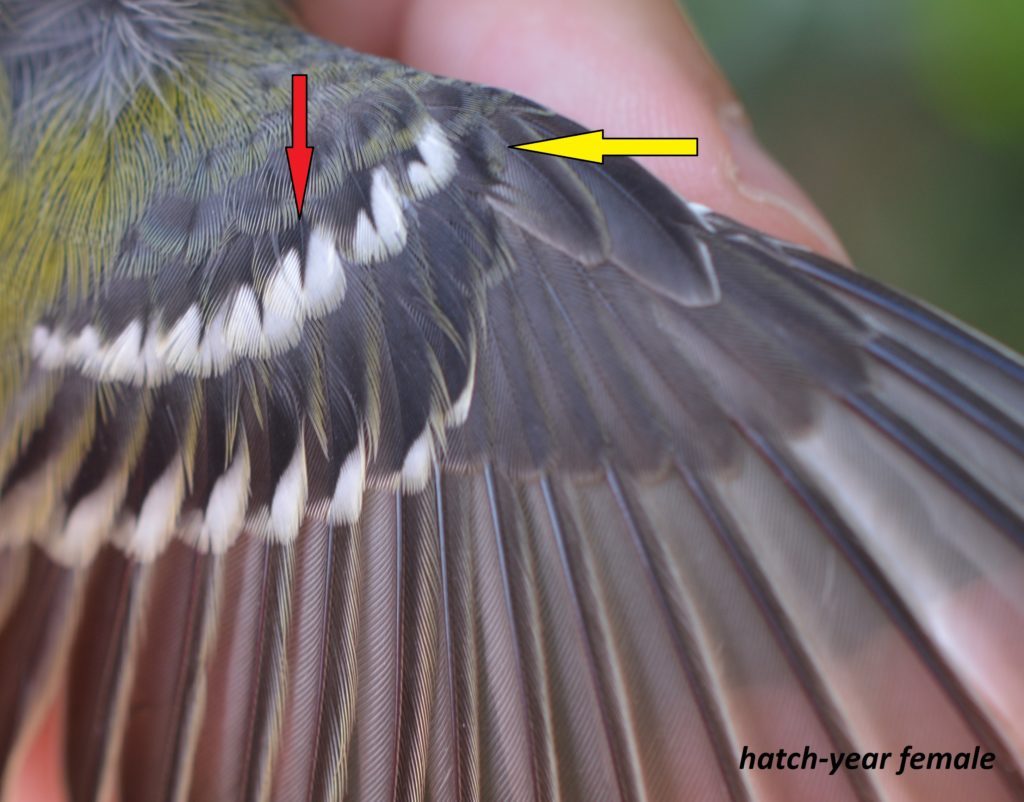

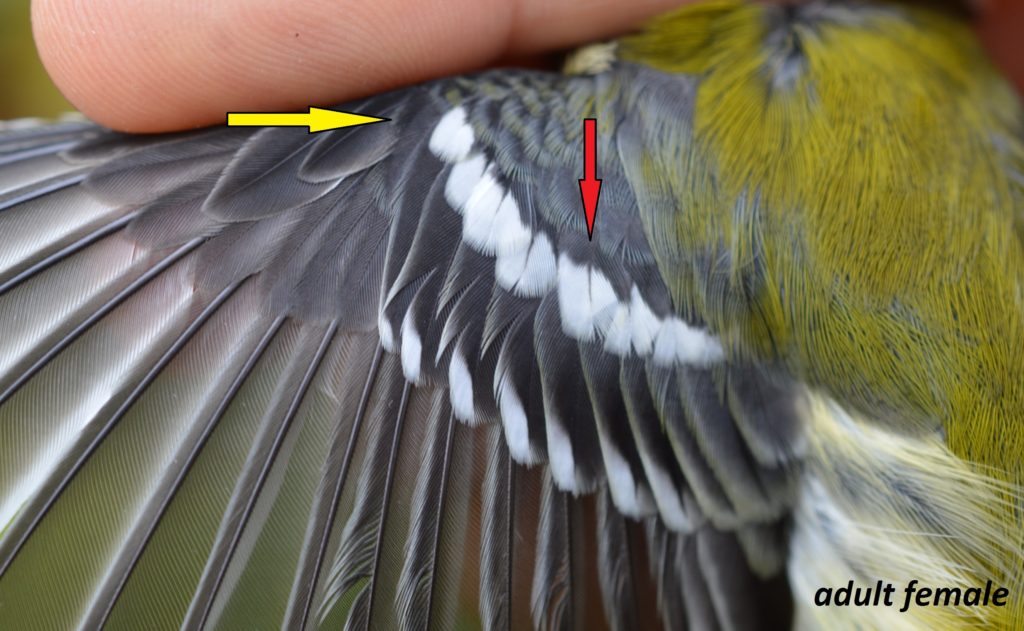

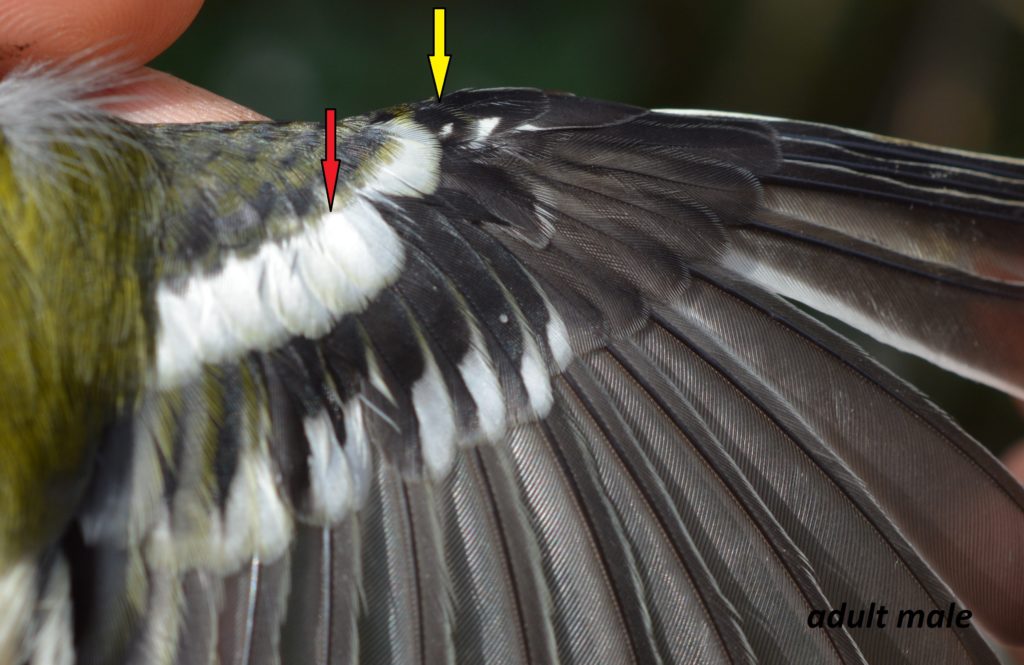

When aging warblers, we are usually looking at the alula feathers, the coverts at the outer edge of the bend in the wing. Most hatch-year warblers will replace the first (smallest, top) alula feather (A1, indicated by yellow arrow in photos) but not the other two alular coverts, which we refer to as an "A1 limit"-- the molt extended through A1, but stopped before A2 and A3. Notice the A1 limit in the hatch-year female wing, but not the adult female. The adults typically replace ALL of their feathers in a post-breeding molt, and therefore do not show a molt limit.

For the Black-throated Green Warblers, we are also looking at wing coverts to help determine the sex. Note the median coverts (indicated by the red arrows) in these same photos. The black center shaft on these feathers is a female trait. This black shaft streak will be absent or reduced in the males of this species. Since the amount of black can be similar in adult female and young males, the rule of thumb is always to age first, then determine the sex.

Of course, these are guidelines and it takes practice and seeing a lot of birds to get proficient at aging birds. And one always has to watch out for something unexpected. For example, if you look closely at the wing of the hatch-year male, you will see this individual broke the 'rule'-- he did NOT replace A1; his molt stopped at the carpal covert, the small covert between the alula and the greater coverts. A good reminder that not all birds molt by the same pattern, not even those of the same species.

The tail can also be helpful in sexing Black-throated Green warblers. Specifically, the amount of white on the outer three retices (R4-R6, numbered from the middle to the outside). Notice that the males have much more white that the females of the same age class. Again, the adult female and young male are similar, reminding us of the importance to age first. In this case though, tail shape also helps us sort them out-- the adult female tail is more broad and rounded than that of her young male counterpart.

Sometimes before we can think about age and sex, we have to pause and consider the species-- there is a reason they are called "confusing fall warblers." Although the crown for which he is named was quite evident in this adult male Orange-crowned Warbler from late October, young birds and females of this sex are easily confused with the Tennessee Warbler.

Watch for faint breast streaking and yellow undertail coverts in the Orange-crowned warbler.

Immature male Orange-crowned and a young male Tennessee Warbler for comparison.

Of course, identification confusion isn't exclusive to the warblers. We band mostly Black-capped Chickadees, but every once in a while we get a Carolina Chickadee; this season we took the opportunity to get some side-by-side photos; in each photo, the Black-capped chickadee is on the right.

In this profile picture, note that the demarcation between the black under the chin and the white of the breast is more clearly defined in the Carolina Chickadee, and smudgy in its Black-capped relative.

Note that the amount of white on the wing coverts and inner flight feathers (secondaries) is much greater in the Black-capped Chickadee.

Carolina Chickadee's have less white on the edge of their outer tail feathers than Black-capped chickadees and, although hard to tell from this photo, the Carolina Chickadees have shorter tails.

We banded eleven sparrow species this fall. The "highlight" from this group was cartainly this young Grasshopper Sparrow. Although they do breed in our county, we rarely capture this grassland species. Our most recent captures were on 8/23/12 and 9/27/14; we banded this individual on August 30th. The Second Pennsylvania Breeding Bird Atlas (2012) notes that this a species has seen a "sharp decline since the 1960's," with "around 70% of the population lost" since the publication of the first Altas ( 2002) due to habitat loss and "changes in grassland management."

Much more common around the lab, Swamp sparrows tend to arrive and stick around for a while, so we took the opportunity to get photos highlighting the age differences in fall plumage. No need to look for molt limits here-- young Swamp Sparrows have less gray on the head and face, with yellow lores; the lores of the adults are whitish gray.

We don't often have to remove bands (once banded, even as a nestling, the bands fit for life), but we did replace this band on Gray Catbird. As you can see in the photo, the last digit, a "6" was well worn and of course we were curious just how old this band (and the bird!) was. First banded on June 16, 2006 as a second-year female (hatched in 2005), she was now 12 years old!

This September encounter with this "old" Catbird was the 15th time we had captured her. In her first three years of life, we caught her in the Spring or Summer, but since 2009 she has consistently shown up in only our Fall totals in the midst of her post-breeding molt. Interestingly, out of all 65 nets open when she visits, we have only caught her in three sets of nets that are close together, situated around our ponds.

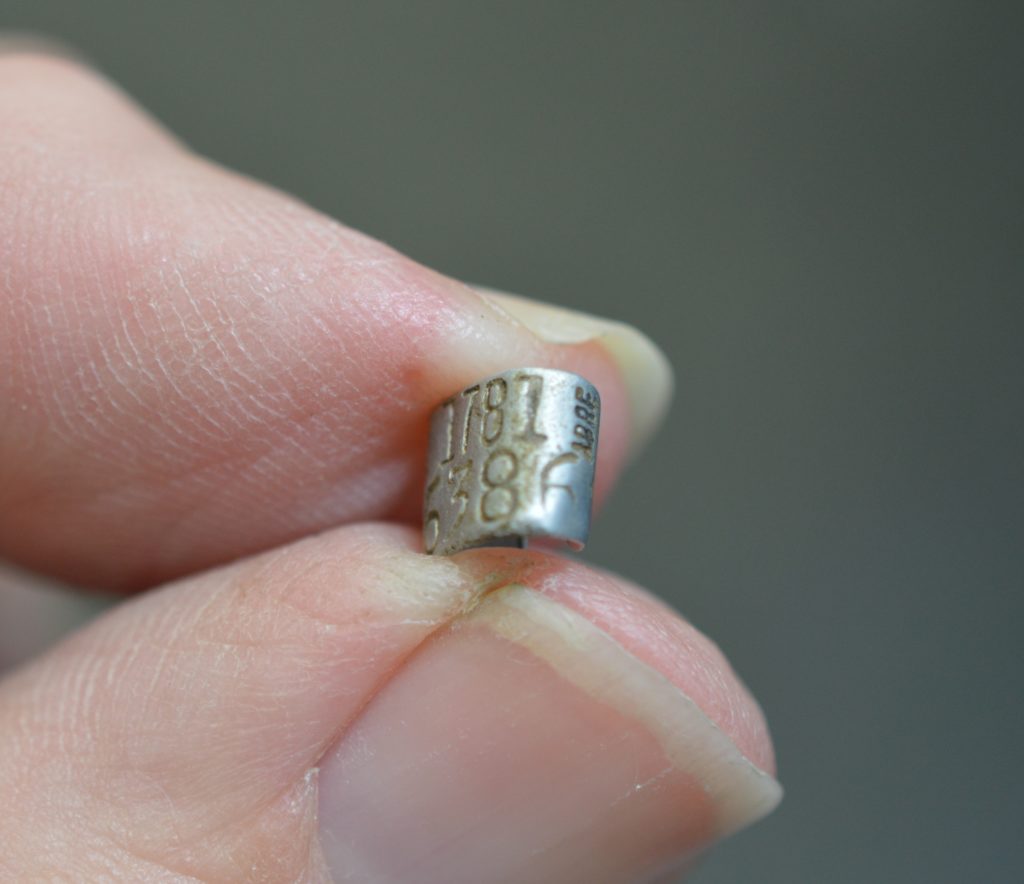

And speaking of bands, have you ever wondered how small our hummingbird bands are?-- VERY small!!

The band shown here is on a young male captured in August. Is it any wonder they are in the family "Apodidae?" While they aren't technically "without feet" their feet are definitely very tiny!

For our last highlight, we've included this adult Black-billed Cuckoo banded on August 25th. Always a fun species to have in the hand due to their throaty vocalizations and unique, almost-tropical appearance, this was one of two Black-billed Cuckoos this season (the second was a hatch-year bird banded on October 12th).