November 7, 2014 - February 28, 2015

Over the winter, the banding station was in operation for 32 days. On nine days we were able to open a small sampling of nets that remain on the poles for winter use. There were 14

days when it was too cold or too snowy to use the nets and we used baited traps (like the one show at the left), and nine other days when we used a combination of nets and traps as the weather changed throughout the morning.

We banded 369 birds across 30 species and processed another 941 birds that were recaptures (previously banded here at Powdermill). The top five species for newly-banded birds were: American Goldfinch (109), Dark-eyed Junco (105), Purple Finch (38), Fox Sparrow (12) and White-throated Sparrow (12).

Pictured: Fox Sparrow (Adult)

Combining data from new and recaptured birds resulted in the addition of 1,310 records to our database. Interestingly, although we banded only a few newBlack-capped Chickadees (11) and Tufted Titmice (2!). These two species were the most likely to be seen in the hands of a bander this winter. We processed 33 titmice a total of 263 times (new andrecaps, remember) and we encountered 47 chickadees for a total of 289 times over the two and a half months. Combined, these two species account for 42% of the data collected all winter, and they didn't even make it into the top five (new) species!

The average number of times that a chickadee or titmouse was recaught over the winter was about 7, but we had four individuals that were each recaught 29 times. Sometimes we

catch a bird so often that we get to recognize its band number, but we were able to identify the Tufted Titmouse

pictured here because its plumage was, well, "Odd." Hence, we named him "Todd."

You probably already realized this picture was not taken during our winter season-- this was our first encounter with "Todd" (July 17th, 2014), when he had just fledged from the nest (aged "local"). He flew into our nets 8 more times throughout our Summer and Fall banding seasons, and we processed him another 23 times this winter.

Notice how brown this bird's feathers are, as well as the extreme wear on his tail feathers.

Juvenal feathers, which are all grown at once while still in the nest, are always of a lesser quality (not as colorful, less sheen, structurally weaker) than the same feathers on an adult bird. As shown in this wing photo from our first encounter, Todd's feathers were extremely lackluster and already showing wear, even just a few days out of the nest.

Probably a factor of poor nutrition while these feathers were growing, it is interesting to note that things seem to have improved before this bird left the nest since the flight feathers show the more typical gray color on the section of feather closer to the body (the part that would have grown in last). This color difference was more obvious in this photo from a re-encounter with Todd on September 8th.

By the time we found Todd in one of our traps on December 11th, he was looking a little better, having replaced some body feathers in late fall, but the retained feathers of the wing are even more degraded and faded. Note though, that four on the inner secondary flight feathers were replaced.

Close-up shots of the very brown juvenal primary coverts (left) and flight feathers with the contrasting replaced secondaries atop (right).

Todd's tail was in even worse shape than his flight feathers, as seen in this series of photos, beginning with the date of banding, July 17th, 2014.

By Septmber 8th, most of the tail was being replaced (note the one remaining juvenal retrix on the right, and the fresh gray retrices, some still in sheath).

Full grown tail, looking pretty sharp against the snow on February 26th.

This photo, taken in December shows Todd in a little better shape, with replaced tail and body feathers.

We must mention here that Tufted Titmouse plumage is not sexually dimorphic, which means that both sexes look identical and can only be identified as male or female by the presence of breeding condition. We are hoping that "Todd" will stay with us through the Spring and into the Summer so that we can see if perhaps he (she?!) should have been "Maude, the Odd Titmouse."

Although we did encounter a lot of Black-capped Chickadees this winter, its close relative pictured here, the Carolina Chickadee was a nice surprise. Banded on December 30, the last banding day of 2014, it was our very last "first of year" bird.

Quite common just a short drive from here, Carolina Chickadees are not often seen in our neck of the woods. Although the two species of chickadees can be difficult to separate while flitting around through the trees, we can use wing and tail measurements as well as a few subtle plumage differences that are more obvious while the bird is still in the hand.

One of the most helpful plumage characteristics for species identification is the amount of white on the greater coverts (the lowest group of feathers covering the flight feathers). In the photos to the left, the Carolina Chickadee wing is on left left (note the absence of white on the greater coverts) and the Black-capped Chickadee wing is on the right.

A look at the Black-capped Chickadee (compare this to the photo above of the Carolina).

Another bird that we capture only occasionally over the winter (averaging one or two a year) is the Mourning Dove. This year we were quite lucky and captured eight!

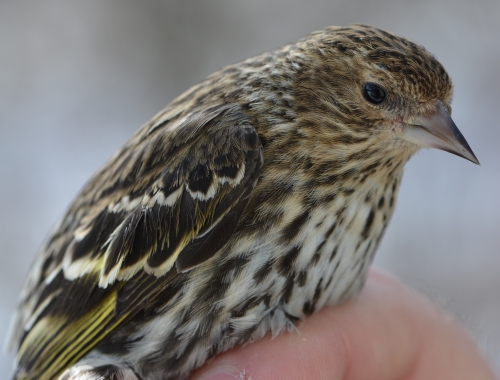

The presence of Pine Siskins at Powdermill can vary from year to year, but they are always a welcome addition to the banding totals. The winter range of these finches changes in response to seed crops. This year we banded only five.

Although these birds look fairly plain when visiting our feeder, we think they look pretty handsome up close with their streaking and yellow highlights.

| Another bird with subtle but beautiful plumage is the American Tree Sparrow. The rusts and warm browns of the sparrows are quite striking, as this sparrow seems happy to display. This was an adult bird (note the characteristic rounded adult tail) that we banded on November 11th, in our first week of winter banding. We banded six American Tree Sparrows in all this season.

Since these sparrows breed in the far northern Tundra, we saw our last of them on March 12, but we look forward to their return in the Fall. |

If you are able to get a good look at it, the bi-colored bill of the American tree Sparrow is a good field mark for this species-- dark on the top, yellow on the bottom.

Red-bellied Woodpeckers are always fun to watch at the feeder and we were fortunate to band four this winter; three females and one male.

The females of this species (pictured at left) lack the red color on the crown of the head whereas the males have a continuous red patch from the beak to the nape of the neck.

Although named "red-bellied" it isn't often that the red on the abdomen can be seen, and when it is, the red is usually quite faint. However, the red on the 'belly' of this bird was quite distinct and extensive. Not surprisingly, she was an older bird (Third-year).

We have mentioned the remarkable woodpecker tongues in previous posts, but we still wanted to share this photo highlight showing the sturdy beak and bristled tongue. Note too, that the tongue has two sections-- a grayish, bristled outer end with a fleshy pink base. The gray part of the tongue is quite sturdy, resembling a soft plastic; this helps the woodpecker when it is probing drilled holes for insects. What a great adaptation!

Each season at Powdermill is different and gives us a chance to learn new information about the species we are lucky enough to encounter each day.

Even in the midst of a late-Winter snowfall, it is nice to see that some birds are already beginning the process of nesting. Looking forward to the Spring and all of the new birds that will come our way.

We were fortunate to have extra staff this winter to help us with some lab testing and data review. Pictured at left, banding a Dark-eyed Junco, is our intern from Germany, Luka Schröder, who was with us for for four weeks this winter.

We were also grateful that Margaret Rhode, one of our Fall seasonal banding assistants (pictured on the right, in the lab at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown), was able stay on with us until the end of January.

We couldn't have accomplished all that we did this winter if it hadn't been for these two women and all of our wonderful volunteers! Many thanks!