March - May 2015

| During the Spring, the banding station was open for a total of 61 days on which we banded a total of 2,004 birds of 100 different species. Our top ten species, accounting for over half (1,092) of all birds banded this Spring were: Ruby-crowned Kinglet (241), Cedar Waxwing (147), Magnolia Warbler (140), Ruby-throated Hummingbird (124), American Goldfinch (109), Gray Catbird (88), Swainson’s Thrush (73), American Redstart (58), Dark-eyed Junco (56), and Red-eyed Vireo (56).

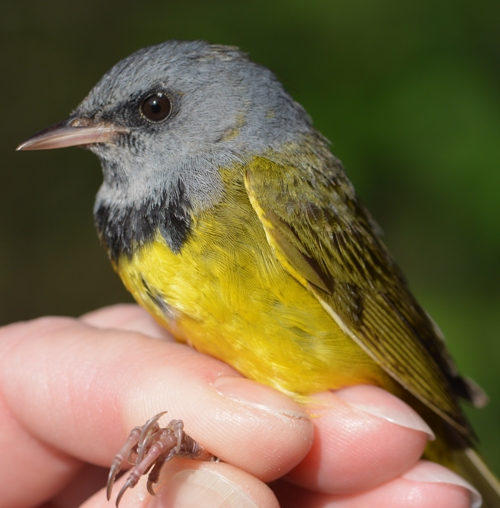

In addition to new birds banded, we also collected data on 1,373 recaptured birds for a total of 3,379 birds processed this season. Spring abruptly shifted in the beginning of May from north winds and below-freezing temps to south winds and highs in the mid-80’s. As a consequence, many of the migrants likely overshot us when the winds were favorable. Across the last 10 years, 2015 would rank as 8th for newly-banded birds and 2nd for recaptures. Pictured: one of our "Top 10" species, an adult Gray Catbird banded May 2nd |

Interestingly, this year, far more first-of-year species were returning birds that had been banded in prior years.

These included Eastern Phoebe, Louisiana Waterthrush, Blue Jay, House Wren, Common Yellowthroat, Yellow Warbler, American Redstart, Hooded Warbler, and Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Ironically, although the Eastern Phoebe is always one of the first migrants we hear in the Spring, we wouldn’t actually band our first this year until the first week of our Summer season when we banded a fledgling.

[Pictured: adult Eastern Phoebe, recaptured on April 7, first banded at Powdermill last September]

But we weren’t thinking about fledglings or even first-of-year birds in late March/early April when we spent a few days engaged in habitat maintenance. Much of the value of our 54-year data set is the ability to track changes in bird populations and morphology. Therefore, it is very important that we keep the habitat around the nets consistent from year to year so that our long-term data reflects population, regional habitat, or climate changes, not local habitat changes.

Several times per year we break out the loppers, saws, and wood chipper to thin out the vegetation and lower the overall height to the approximate height of our nets. This keeps our banding area in a state of early successional habitat and ensures that the birds are foraging down near our nets and not simply flying over the nets in taller vegetation.

In addition to the first-of-year recap Phoebe, we had a few other typical harbingers of Spring, including this handsome adult male American Robin banded on March 29.

Often heard before they are seen, the vocalizations of the Red-winged Blackbird always let us know that Winter is on its way out and Spring is here! We banded this second-year male on April 12th, although this species had been heard around the lab for several weeks prior. This individual was one of 18 that we banded this season.

As mentioned earlier, this first-of-year Louisiana Waterthrush that flew into our nets on April 7 was already banded. The metal band and the color bands seen in the photo at left were applied by a research crew working at Powdermill studying the effects of stream acidification. More recently researchers here and statewide are monitoring Louisiana Waterthrush populations to study the accumulation of toxins associated with unconventional gas wells.

Our first encounter with this bird was on July 18, 2010, when it was aged adult, making him more than six years old at the time of this photograph. It seems he is very faithful to breeding grounds near the lab, since we have seen him every Spring since 2010.

In addition to the Eastern Phoebe, we were able to capture images of several other flycatchers this Spring, including this second-year Least Flycatcher banded on May 14.

Flycatchers sit quietly on a branch waiting for an insect to fly by and then soar out and snatch their prey in flight. Notice the specialized feathers around the bill that look like fine black hairs. These are rictal bristles and probably provide protection for the bird’s eyes from wriggling insects. They also act as feelers to help the bird direct the prey into the bill since their depth perception is poor owing to the placement of their eyes on the sides of the head rather that the front like a hawk or human. This placement makes them superior at detecting predators approaching from the rear.

“Trail’s Flycatcher” is the name given to the combined Alder and Willow Flycatchers since they cannot be differentiated in the hand—only by song in the field.

This adult Traill’s, also banded on May 22, is showing off the other great adaptation flycatchers have for their on-the-wing feeding—a nice wide bill!

Athough it doesn’t have flycatcher in its name, this Eastern Wood-Pewee from May 20 is still considered one of this group, and has the same feeding habits. Notice the characteristic dark tip on the underside of the bill.

We also photographed several species of the vireos we encountered this Spring, some of which we only see on migration. Notably absent from our totals this year was the Blue-headed Vireo, although they were heard in the vicinity on more than one occasion.

Pictured here is a an adult White-eyed Vireo banded on April 24.

This warbler-sized second-year Philadelphia Vireo banded on May 22 was one of twelve that we encountered this Spring.

Often confused with the Philadelphia Vireo, the Warbling Vireo lacks the yellow wash of color over the throat and breast. This Warbling Vireo, which flew into our nets on May 15, was the only one of this species we banded this Spring.

Though they arrive late to the migration party, we are still much more likely to catch the Red-eyed Vireo than any other vireo species. We banded 56 this season, even though the first arrived on May 6, allowing them just over three weeks to achieve Top 10 status.

This bird shows another adapted feather, not unique to vireos, but seen often across many different species. Notice the fine hair-like feathers rising away from the body at the nape of the neck. According to Cornell’s “All About Birds” website, filoplumes are “feathers [that] lack specific feather muscles but have sensory receptors next to the base of the feathers. Filoplumes lie under the contour feathers and are thought to provide the bird with feedback on contour feather activity.”

We also photographed a few species with plumage that is interesting not because of adapted feathers but because the plumage is so colorful and varied. The Northern Flicker (pictured at left) has one of the most intricate and beautiful plumages that we encounter. We were lucky enough to band six flickers this season, this one was the first, on April 8th.

The four pictures at left illustrate some of the details of the plumage of the Northern Flicker.

We particularly like the fact that the undertail covert feathers have black heart-shaped spots (lower right)—how cool is that?

Another bird with lots of detail in its plumage color is the Cliff Swallow. This individual, banded on May 29, was our first Cliff Swallow since 2001 and our 26th ever! Quite a catch for one of the last few days of Spring banding!

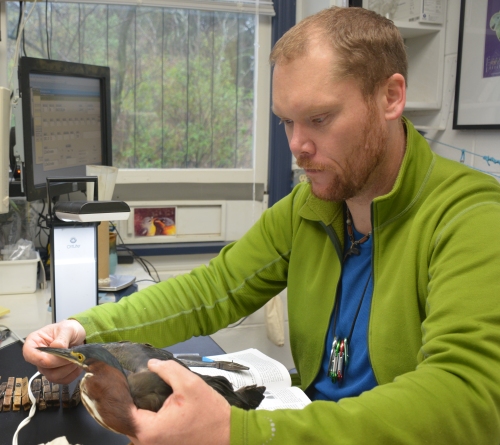

On May 1st we caught and banded our first Green Heron since 2012. Seen here, banding coordinator Luke DeGroote examines the plumage of the heron to determine its age.

And of course, up close, the Green Heron also has a stunning mix of colors and patterns, in addition to a beautiful yellow-orange eye. Just be careful of that long powerful bill if you want a closer look!

While we have featured the adapted feather tips of the Cedar Waxwings before, we have never encountered one with this unique plumage—yellowextensions on the tips of the inner flight feathers instead of the usual red. We banded this unique individual, an adult male, on May 20.

A close-up of the yellow tips of the Cedar Waxwing.

One other note about color in plumage: while most color is deposited into the feather in the form of melanins (like our skin color) and carotenoides (like our hair color), some colors are entirely structural. In other words, the barbs and barbules of the feathers arrange in a manner that reflects a specific color.

This Ruby-throated Hummingbird from May 16 is a good example of changes in color as the direction of the light changes. Both photos are of the same bird, each from a slightly different angle.

Another ‘structural’ pigment is found in the blue of the indigo bunting. This adult male from May 30 was so handsome we couldn’t help but take his picture.

The blue of the Eastern Bluebird is the same—only vibrant and truly blue when seen in the proper light. This pair of bluebirds, photographed in the early morning light on April 12, were busy building a nest in a box at the edge of one of our small ponds.

Two days later we were able to take a closer look at them… both were second-year birds (hatched in the summer of 2014). We banded the female that day, but we had actually banded the male a month earlier, on March 12, perhaps while he was scouting for nesting territory. It seems she approved of his choice!

Our only Eastern Kingbird for the season, an adult female, was banded on May 15.

This individual, encountered on April 29 was another rare capture for us, the Savannah Sparrow. Notice the yellow facial pattern and the short, notched tail. Savanna Sparrows are uncommon here because of the limited amount of grassland habitat. Fun fact: Did you know that Savannah Sparrows get their name not for its affinity for grassland habitat but because Alexander Wilson collected the first individual in Savannah, Georgia?

We average just one or two Pileated Woodpeckers each year, and this one might have escaped our nets had it not been for our fast-acting banding coordinator, Luke DeGroote, who took off at a run when he saw it hit the net. Birds this large can often self-extract or will simply bounce off the net and fly on their way. We had to snap a quick shot of this after-third-year female before releasing her. She already had a brood patch, indicating that she was most likely incubating eggs.

Another bird that is frequently seen flying around the ponds but rarely banded is the Belted Kingfisher. This adult male flew into a net on April 9th; he was one of three kingfishers we banded this Spring.

By mid-May things started to get a little, well, Cuckoo! In the past, we have averaged just one or two Yellow-billed Cuckoos each Spring, with its close relative, the Black-billed Cuckoo being more common. However, this season we did not band any Black-billed but were able to net ELEVEN Yellow-billed Cuckoos. The individual pictured here was our first, on May 13.

The same Cuckoo, showing the warm rust color visible on the extended wing.

We were surprised to capture two more cuckoos the next day, May 14; we caught the other eight in the next two and a half weeks. Several of the cuckoos could be heard around the banding area for most of this time.

Cuckoos eat hairy caterpillars, which seem to be quite abundant around the lab this year. A cuckoo can eat as many as 100 tent caterpillars in a sitting; to get rid of the spines that get stuck in their stomach, they periodically regurgitate their stomach lining, spines and all.

Banding Coordinator, Luke DeGroote, shares the excitement of the cuckoo invasion with his son, Oak.

This second-year male Orchard Oriole from May 20th was the only one banded at Powdermill this Spring.

And while we are featuring Orioles, we couldn’t help but include this handsome adult male Baltimore Oriole banded on May 9.

This colorful second-year male Rose-breasted Grosbeak was one of only two that we caught this Spring, making it a lower-than average season for them.

This handsome second-year Hermit Thrush is a good illustration of the warm brown plumage and the distinctive red tail that helps birders separate Hermits from the rest of the thrushes. This was one of 13 Hermit Thrushes we would band this season.

Of course there are many birds around that we don’t catch but do enjoy watching and occasionally try to photograph as time allows, like these three Bufflehead ducks (two males and a female) that spent a few days on Crisp Pond.

And this Osprey that gave us some awesome views while hovering above the same pond.

The resident Canada Geese were quite entertaining this year. Turf wars over the island in Crisp Pond led us to believe this must be the best piece of real estate by goose standards. We like to think the goose pictured at the far left was just as confused as we were by a late-Spring snowfall (April 22!).

There were two pairs that successfully nested on property and the goslings of both hatched on May 15, eight total.

A photograph of our banding assistants marveling at the late-April snow—see, same puzzled (disgusted?) expression as that goose!

OK, well in case you were wondering, yes we did catch some warblers this Spring in all their wondrous bright Spring attire, and how could our "Pictorial Highlights" not feature a few of those?

For your review, we present a few of the elegant warblers which on any day are a nice surprise in the net.

Leading the pack is this subtle diminutive female Orange-crowned Warbler, the only one banded this season (from May 16).

This adult female Black-throated Blue Warbler, while not as stunning as her male counterpart, has some very pretty blue highlights on the wing and the edge of the tail feathers.

Once thought to be a separate species, James Audubon wrote: “The birds represented in Plate 148 of my large edition as Sylvia sphagnosa, are the young of the Black-throated Blue Warbler, the female which resembles them so much that I looked upon it as of a species distinct from the male.”

This individual from May 5th was one of seven we banded this season-- 6 females and one second-year male.

This Lady was "one, singular sensation." A second-year female, she was the onlyBlackburian Warbler we banded this Spring, and we had to wait until May 23 to admire her!

Roger Tory Peterson fondly referred to them as "fire throats". It's easy to see why. The males blaze even brighter but we'll take the delicate tangerine mixed with black and grey appearing on this lovely lady.

The Male Bay-breasted warbler pictured on the far left set a record-early arrival date when we banded him on May 6th.

As is often the case, the female arrived a little later, on May 17th. Both were second-year birds, and these were the only two Bay-breasted Warblers we caught this Spring.

We banded five Mourning Warblers this season, all within the latter half of May. Pictured at left is an adult female.

This second-year male was banded on May 14th.

And an adult male, the most colorful, banded n May 12th.

A few more adult males showing off their spiffy breeding plumage...a Black-throated Green Warbler from April 23rd, one of seven banded this season.

This handsome Yellow-Rumped (Myrtle) Warbler banded on April 29th was the first of three that we would catch in our nets for the Spring.

A striking Canada Warbler from April 30th. These warblers were a little more abundant; we banded 31.

Since Cerulean Warblers are never a common capture, we wouldn't miss a chance to include this handsome adult male in our highlights. He was banded on May 27th.

This distinguished male American Redstart was banded May 28th, 2010 as a second year bird, so we know that he was almost 8 years old when we re-caught him on April 25th! (The oldest known American Redstart lived to be at least 10 years old.)

Since this was a very special last bird of the day on May 13th, we'll make it the last warbler of our Spring highlights. We often hear Yellow-throated Warblers singing from the tops of the pines around the banding lab, but this was our first banded since 2008! It was a second-year male.

In addition to our daily routine of banding birds, it was a busy Spring for us. We hosted various family and school groups at the lab, resulting in 232 visitors to the lab, most for the first time.

We also offered two workshops, with a total of 15 banders-in-training from across the country.

Participants learned how to handle, extract, band, measure, sex, and age wild birds. These workshops allow us to impart the knowledge we've acquired through years of experience to help ensure that bird banding practices are beyond reproach. We encourage precise data collection so that in the end, the data collected can be used to conserve birds.

A group photo from our Beginner Workshop. Shown kneeling in front, middle is Annie Crary, a former bander at Powdermill, who returned to share her knowledge as she assisted with the training. She is surrounded by workshop participants, PARC staff, and visiting bander Eugene Hood (standing, far left).

We also continued our research with bird-safe glass this Spring.

Shown here is our Flight tunnel where birds are safely videographed while making a choice between a treated pane and a clear pane of glass. Birds are released at the right and fly to the left side where they are gently stopped by a net before hitting the glass panes.

We were able to run 1,185 flights in the tunnel this Spring, adding to our data supporting safe glass for birds.

Pictured at the far left, tunnel tech Lauren Horner explains the glass research to a group of visitors.

If you would like to find out more about our bird-safe glass research, check out the article, "Saving the Songbird," featured in the Summer 2015 issue of the Carnegie Magazine which can now be viewed online.

We are also collaborating with Professors Jill Henning and Christine Dahlin from the University of Pittsburgh in Johnstown.

They are researching tick-borne diseases. We often see birds carrying ticks, usually around the eye as seen here on this Brown Thrasher. The ticks are carefully removed and sent to the lab for analysis.

In addition to a healthy cadre of faithful volunteers, we were fortunate to be joined by two visiting banders this Spring, pictured at left, each with a "Lifer" bird that had previously been a nemesis bird.

On the left, Laura Marie Koitsch, a former PARC banding assistant, was lucky enough to be here when we caught two cuckoos.

Eugene Hood, a visiting "Ringer" from England had missed seeing a Cerulean on several trips to the US, but not this time!

Many thanks to both of them, and all of our volunteers for the help that they rendered this season. We couldn't have done it all without you!

Without really trying, we managed to get color-coordinated for the end-of-season picture on the last day of May.

Pictured in blue, two of our faithful volunteers, Jim Bernat and Debbie Ball, who visit us from Virginia once or twice per season. Showing off the white official Powdermill tees are seasonal staff, Lauren Horner (tunnel) and Martin Beal. And at the flanks in yellow, our year-round staff, Luke DeGroote (banding coordinator)and Mary Shidel (banding assistant).

That last day of banding also gave us a special treat and a glimpse of things to come as we head into our Summer banding... on one of the last net runs for the Spring, Martin managed to flush two young turkey poults into the net. They were pouty, soft and fluffy and adorable!

Upon returning the youngsters to the area where they were found (where mama was waiting patiently), they found a third poult in the net.

Unfortunately, as is the case with many larger birds, the adult female went through the net!

While we had them in hand, we couldn't resist getting a picture of their large, fleshy feet. Like a puppy with big paws, we assured them that they would grow into them eventually!

Enjoy your summer. Have fun. Go birding. Watch out for young fledglings on the roads and trails and don't disturb them (unless they need a lift out of the centerof the road)...their parents are probably very nearby looking for their offspring's next meal.

We'll be out checking our nets over the summer; if we get anything interesting, we'll be sure to photograph it and share it with you later this year.

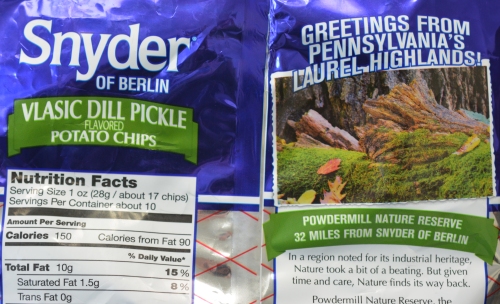

If you're bored while you are waiting for the Summer Pictorial Highlights, you might want to kick back with a bag of Snyder's Dill Pickle Chips. Powdermill Nature Reserve was fortunate to be featured on the back of them!

Oh, and be sure to "Like" us on Facebookfor periodic quick updates.